It was all about the racing. For Fred and Augie Duesenberg, it had always been about the racing. During the turbulent Model A years in Indianapolis, the racecars had come first and foremost. And they had won when the company had failed. After E.L. Cord entered their lives the racecars became a little less important, but Fred brought the racing cars to the Model J with the addition of his centrifugal supercharger introduced on the SJ in 1932, a feature he had employed as far back as the 1920s. Sadly, Fred would not live to see the greatest achievement of his supercharged Model SJ. He died from complications following a traffic accident in July 1932.

With the introduction of the Model J Duesenberg in December 1928, Fred’s attention was drawn away from the racetrack, and though the company continued to compete, the glory days seemed to be over. By 1929 Harry Miller’s cars were dominating Indy and most of the races around the country. The supercharged Duesenberg straight eights, however, had left their mark on motorsports history, and on Indianapolis. Even after the introduction of the Model J, Fred kept his hand in the racing program at Duesenberg Brothers, located across the street from Duesenberg Inc. He produced a handful of racecars based on the Model A, two of which were purchased by Pete DePaolo, and at one time there were no fewer than eight qualifiers for the Indianapolis 500 equipped with Duesenberg Brothers engines or chassis. In 1931 there were 16 cars on the entry list with the Duesenberg name, one of which finished second, less than a minute behind the winner. Most Duesenberg racecars, however, were seeing the dust of Millers ahead of them at the finish line and by the early 1930s the company’s involvement with racing was over. Fred retired from racing after the 1931 Indianapolis 500, although Augie remained deeply involved, as did Fred’s son Denny.

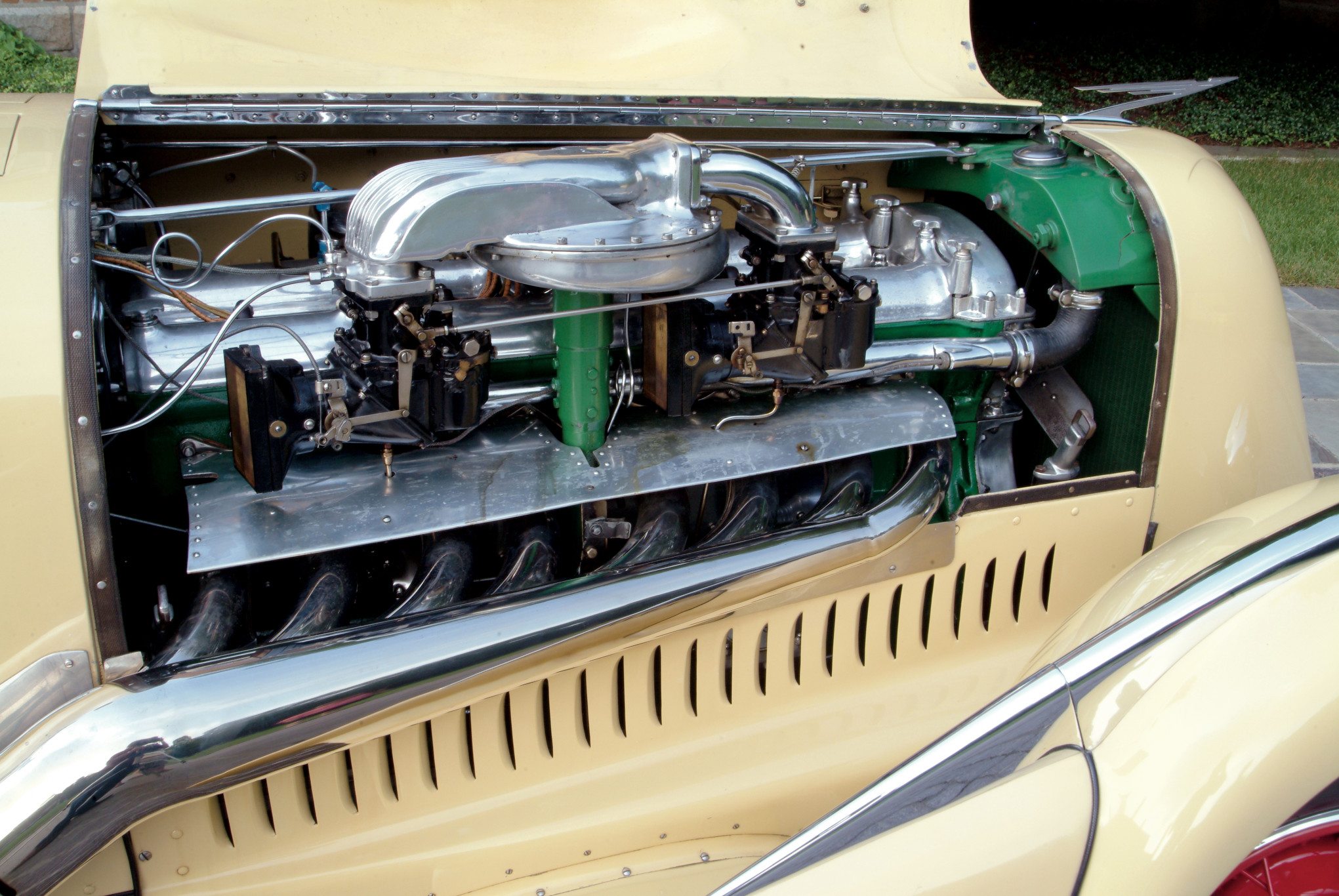

In 1932 Duesenberg introduced the supercharged Model SJ, Fred Duesenberg’s crowning engineering achievement. The centrifugal supercharger, designed by Fred Duesenberg, ran at six times the engine speed, increasing manifold pressure eight pounds at 4000rpm and boosting engine output to a remarkable 320-horsepower.

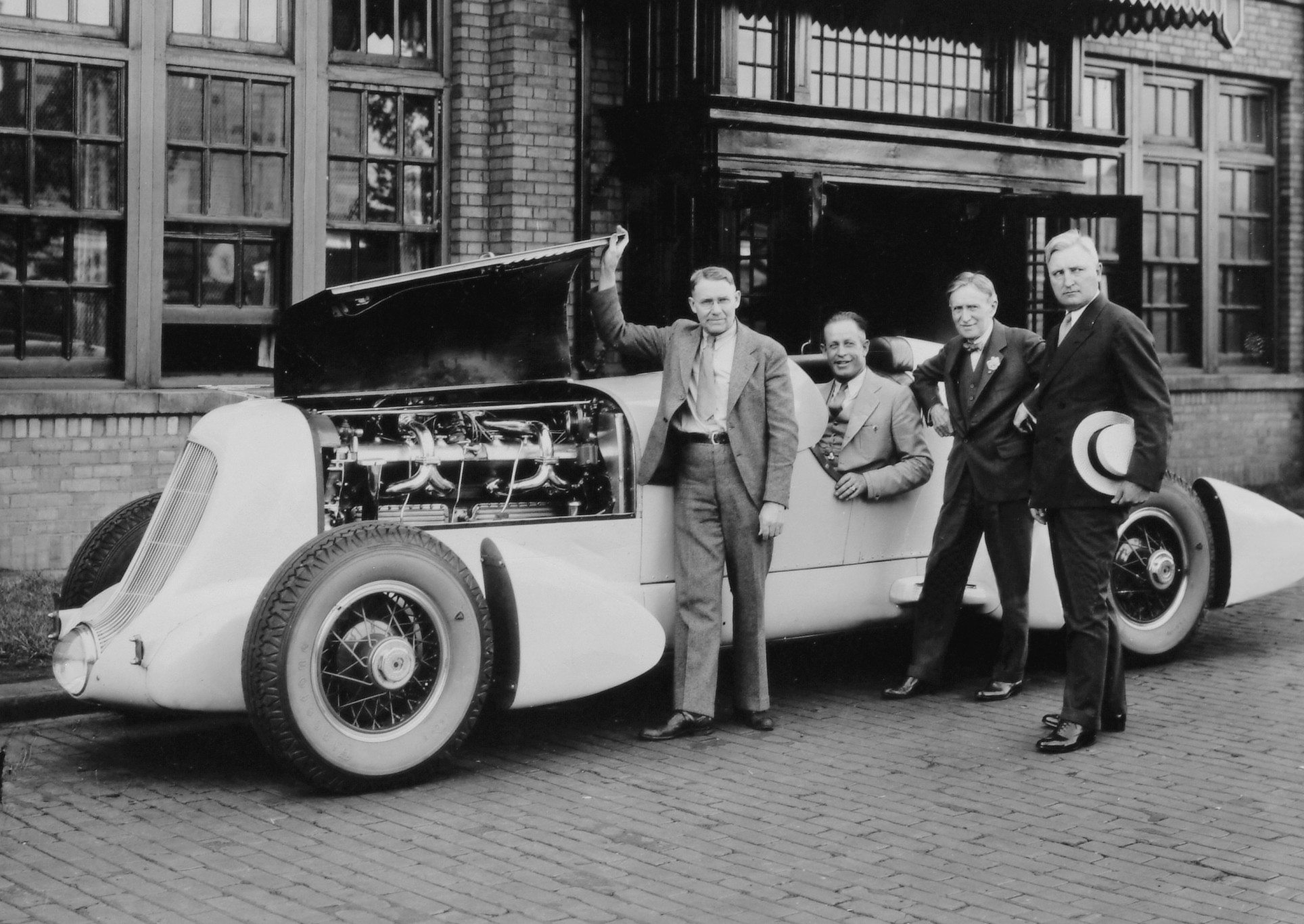

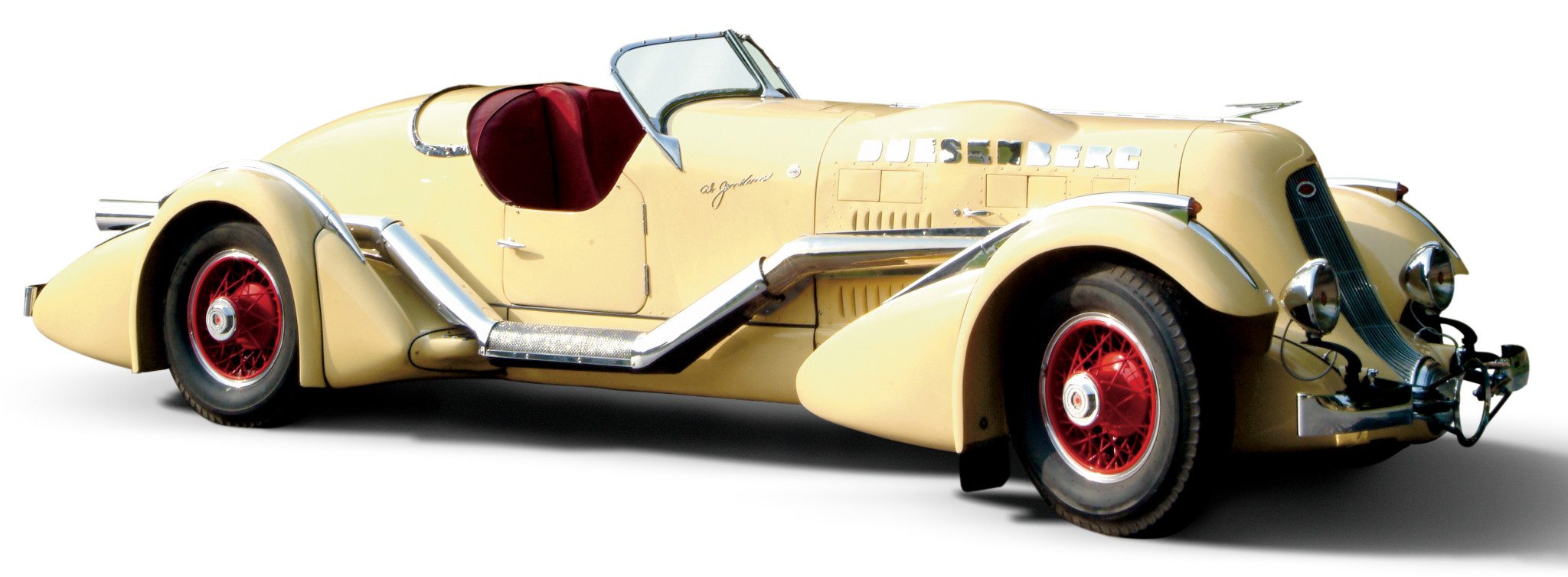

Working for Duesenberg, Inc. by the mid-1930s, Augie still remained involved with racing and motorsports, and three years after Fred’s death in July 1932, he spearheaded a bid for the land speed record at Bonneville with driver Ab Jenkins and a remarkable supercharged Duesenberg Special known as the Mormon Meteor. A new chapter in the history of Duesenberg racing was about to be written.

It was August 31, 1935, scorching 120° heat was radiating off the glistening white salt flats, sending a wall of translucent distortion weaving skyward across the miles of barren terrain. In the distance, the sound of an engine shattered the still desert air like rolling thunder and a streamlined fuselage materialized, ghost like through the vortex of thermal reflection, hurtling past the timers at nearly 160mph. Over the next 24 hours David Abbot “Ab” Jenkins, already America’s number one speed record holder, would record an average speed 145.47mph on a 10 mile oval course laid out across the Bonneville Salt Flats. The distance traveled by Jenkins and the Duesenberg Special over 24 hours was 3,262 miles, nearly the equivalent of driving coast-to-coast in one day. Jenkins also established a new one-hour speed record of 152.145mph, breaking the previous one-hour speed of 134.9mph set in March 1934 at the Avus Ring in Germany by Hans Stuck, who was driving the brand new Auto Union racecar designed by Ferdinand Porsche.

Jenkins’ record setting run was more than another test of man and machine, it was proof of the supercharged Model SJ Duesenberg’s capabilities. It was the embodiment of everything Fred Duesenberg had spent his life creating. It was his legacy. Though built for the Bonneville speed and endurance trials, with mechanical modifications engineered by Augie Duesenberg and a spectacular body designed by J. Herbert Newport, the Duesenberg Special was little more than a modified Model SJ. It had the first SJ engine to be equipped with two duplex carburetors, special ram’s horn manifolds, a higher 7.5:1 compression ratio, and Federal-Mogul insert bearings. For Jenkins’ speed runs it was also set up with different cam timing, a 3:1 rear end with straight bevel gears, and dual fuel pumps with independent fuel lines. Horsepower with the supercharger engaged was estimated at between 390 and 400 at 5000rpm, based on a Duesenberg dynamometer test conducted in May 1935. The car was specially equipped with a dropped tubular front axle and 18-inch wheels, instead of the production model’s 19-inch wheels. The chassis was never given a serial number and the only numerical reference is the engine, J-557.

From a standpoint of aerodynamics, which was still very much an unrefined art and without the aid of a wind tunnel, Newport and Augie Duesenberg had theorized that an angled grille shell, single, integrated headlight, (selected from the 1935 Auburn parts bin!), full-length louvered belly pan, and a tapered tail would significantly contribute to reduced aerodynamic drag. Although the car has never been tested in a wind tunnel, it is very likely that Herb Newport’s design did indeed contribute to the Duesenberg Special’s stunning performance in 1935.

Later that year a contingent of British competitors came to Utah to challenge the Meteor’s one-hour and 24-hour records. Captain George E.T. Eyston and John Cobb, piloting speed record cars powered by aircraft engines, came away from Bonneville with little accomplished. Cobb’s Napier-Railton, powered by a 12-cylinder Napier aero engine three times the displacement of the Duesenberg straight eight, recorded a one-hour speed of 152.116mph and a 24-hour average of 134.85mph, both inferior to Jenkens’ times in the supercharged Duesenberg. Captain Eyston’s Speed of the Wind, powered by a 12-cylinder Rolls-Royce Kestrel aircraft engine, managed to top the Meteor’s hour by 7.2mph and the 24 hours by 5.05mph. But it was a short-lived triumph. Jenkins and the Duesenberg Special, which had been christened the Mormon Meteor following a name contest conducted by the Salt Lake City Desert News, returned to Bonneville in 1936 fitted with a 12-cylinder, 650 horsepower Curtis Conqueror aircraft engine, (what was good for the Brits was good for Jenkins and Augie Duesenberg) sweeping away all of the previous year’s records in every category from 50 miles to 48 hours.

Despite the fact that most of Jenkins’ records were re-established without the original supercharged SJ engine, his achievements at Bonneville with the Special were the fulfillment of both Fred and Augie’s long-time passion. Augie continued to work with Ab until 1938 when they retired the Duesenberg Special. Jenkins purchased the original Mormon Meteor with engine J-557 reinstalled, a windshield, doors, and more stylish fenders added, and logged another 20,000 highway miles before parting with the car in 1943. Changing hands several times in the 1940s, the Meteor finally became part of the Royce Kershaw collection in 1959 and has remained in the Kershaw family until this year, when it sold at auction in Monterey for a record $4.5 million.

Fred and Augie would have been flabbergasted!

(ACD Museum Archives)

by Dennis Adler

(Photos by the Author, ACD Museum Archives, and Ed Lucas III)

© Car Collector Magazine, LLC.

(Click for more Car Collector Magazine articles)

Originally appeared in the December 2004 issue

The Mormon Meteor’s Auction Tale

By Rick Carey

The Duesenberg Special/Mormon Meteor stole the show at the Monterey auctions this year (2004). Offered by Gooding & Company in their first auction, it was what everyone wanted to see, and even more, to hear the rumble of its supercharged straight eight. Speculation about its reception by prospective bidders abounded and rumors sparkled like lightning bugs.

Jay Leno, whose affection for brutally powerful big classics is legend, had a ride during the preview and announced to the crowd upon his return, “OK, you can all go home now. It’s mine.”

The Mormon Meteor crossed the block a third of the way through the Sunday evening Pebble Beach Auction and the tent was crowded. Bidding started high and quickly skated past most bidders’ threshold of pain before settling down to just two bidders: one in the tent and the other on the phone. In the end it was crossing $4 million that brought the bidding to a halt, selling to the phone bidder who was willing to step over the line with a $4,050,000 bid, $4,455,000 with Gooding & Company’s buyer’s commission added on. Now speculation turned to the phone bidder’s identity. It wasn’t the Petersen Museum, and as it turned out Leno was playing to the crowd: it wasn’t him, either.

Only two weeks later the rest of the story was revealed: the successful bidder was a British collector who decided he liked the 1929 Mercedes-Benz SSK offered by Bonhams on September 3, at the Goodwood Revival better. Proving that even for the most deep-pocketed collectors there can be too much of a good thing, some quick negotiations followed among David Gooding and the two Monterey bidders and the Mormon Meteor came back into the waiting hands of the Monterey underbidder, a well-known American collector from the Midwest. With a war chest refilled, the Brit waded into the fray for the SSK…and was outbid when the SSK sold for £4,181,500, $7,480,322, the top price at auction in the last decade. Talk about drama.

If you have a Duesenberg or another collectible you’d like to insure with us, let us show you how we are more than just another collector vehicle insurance company. We want to protect your passion! Click below for an online quote, or give us a call at 800.678.5173.

Leave A Comment