Gather together a group of car enthusiasts and ask them to pick their favorites and you’ll be in for a spirited debate. Any topic this subjective will raise passions, as each argues for and against the merits of one car against the other. In the end, everybody’s right and everybody’s wrong.

So when we decided to pick what we considered to be the most significant pony cars built from 1967 – 1970, we knew we’d be walking into a buzz saw of controversy. Readers would bombard us with letters questioning everything from our reasoning to our ancestry. That’s fine; we always appreciate reader input. But before you begin emailing your opinions, consider our criteria and reasoning, and we think you’ll agree that our choices certainly stand on their individual merits.

We chose to narrow the field to 1967 – 1970 for several reasons. While the Mustang was introduced in 1964 ½, there was no competition for Ford’s first pony car. Plymouth had released the Barracuda two weeks before Ford on April 1, 1964, however, it was a Valiant with a fastback, not truly in the Mustang’s pony car genre.

The second reason is, by 1967, all the major players had entered the pony car field with the exception of American Motors, who would come to market with the Javelin and AMX in 1968. The pony car market was maturing and each manufacturer had built their cars on the long hood/short deck template that Ford had first stamped out in 1964½.

Further evolution of the collective breed could be found in peripheral influences that helped accelerate pony car sales. For the first time, large displacement engines were offered in pony cars, allowing them to enter and compete in the super hot muscle car market. The up and coming Sports Car Club of America’s Trans-Am series was just the ticket for Ford and Chevrolet to wrestle for dominance. By 1970 every pony car manufacturer had smacked fenders in the Trans-Am, which had in three short years passed Formula 1 in popularity in America. Race on Sunday and sell on Monday never had more meaning than it did for pony cars in 1970.

As you read about each of our candidates, we think you’ll agree that the choices we’ve made make sense. Within the context of their time, these seven cars helped shape the destiny of the American pony car.

1967 Chevrolet Camaro Z28

When Chevrolet introduced the Camaro on September 29, 1966, Ford’s monopoly on the pony car market was over. The Camaro measured almost inch for inch to the Mustang, and matched its option list line for line. Its fluid shape highly contrasted to the Mustang’s more chiseled looks.

On December 29, 1966, Chevrolet released the Z28 option to homologate the Camaro for Trans-Am racing. To meet the series’ 305 cubic inch engine limit, Chevrolet combined the bore of their 327 cubic inch block with the stroke of the 283 cubic inch engine’s crank, producing 302 cubic inches. Ridiculously under-rated at 290 horsepower, the Z28’s solid lifter, short stroke engine came alive at 3500rpm and easily zipped right up to 7000rpm.

The Z28 was literally a racecar for the street. Along with the 302 engine, the Z28 came standard with dual, low restriction exhaust, special heavy duty suspension, heavy duty radiator with temperature controlled fan, quick ratio steering, 15×6 wheels on 7.35×15 nylon red stripe tires, 3.73:1 rear gearing and black paint stripes on the hood and decklid.

The Z28 required a host of mandatory options like four-speed gearbox, power brakes (with or without front discs). There were actually four different versions of the Z28 option. The base option as described above cost $358.10. Three others came from the factory with equipment packed in the trunk for dealer or customer installation. A Z28 option with a special air cleaner that ducted to the cowl cost $437.10, with exhaust headers, the price was $779.80, and with plenum air intake and headers, the cost was $858.40.

Chevrolet produced just 602 1967 Z28s, and that was mainly because the dealer body wasn’t even aware of the option. Regardless, the ’67 Z28 established new standards for American performance sedans and laid the groundwork for a new generation of small block, high-performance engines from Ford and Chrysler. Whether on the street or the road course, the Z28 became an instant legend.

1967 Ford Mustang GT

By 1967, the car that started the pony car phenomenon just three years earlier was growing long in the tooth. “It would seem,” Car & Driver noted, “that Ford has been content to rest on its laurels, while the rest of the industry has gone all out to win a piece of the Mustang market.”

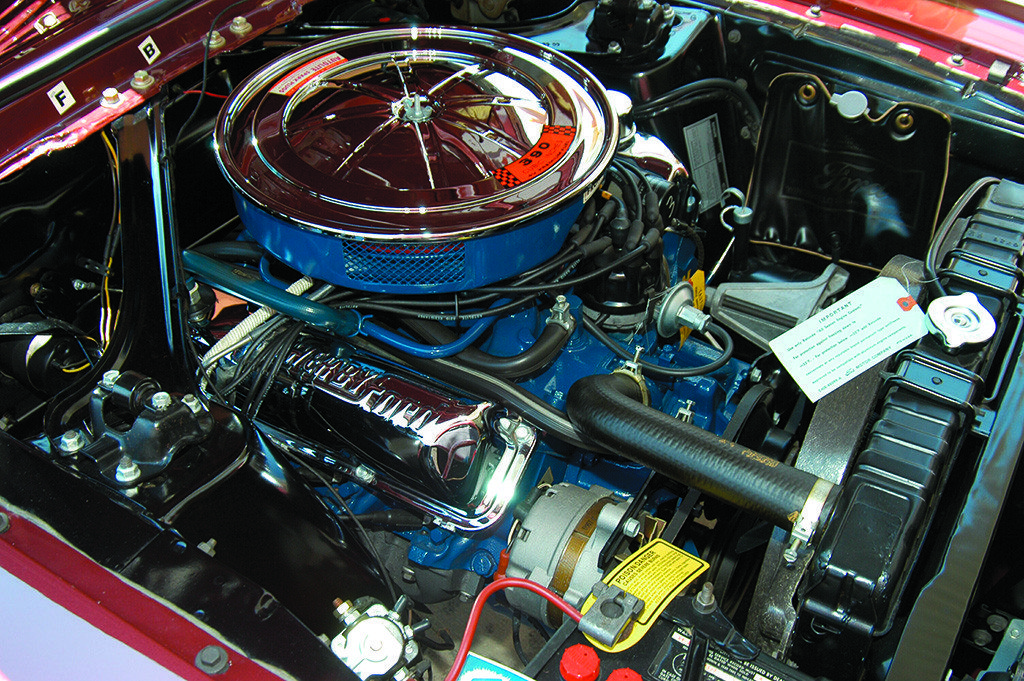

Ford gave the Mustang its first facelift in 1967 in anticipation of Chevrolet’s new Camaro. More important than the cosmetic redo, however, were the engineering changes made under the hood. Ford knew their arch-rival would be coming out of the chute with a large displacement engine option (Chevy didn’t get the 396 V8 out until November), so to remain competitive, Ford widened the front suspension’s girth to allow their 390 cubic inch FE series engine to fit. Getting a big displacement engine into the Mustang was an absolute marketing necessity. Using the “dumb four door” 390 was an absolute disappointment to Blue Oval fans who had hoped to give the Camaro newcomer a solid shellacking on the street. Still, a total of 28,800 Mustangs were sold equipped with the 390 engine in 1967.

Given that the 390 was rated at only 320 horsepower (the base 396 engine had 325 – with options up to 375 horsepower), the Mustang was at a disadvantage. The 390 produced gobs of torque (427 lbs.-ft. @ 3200rpm) great for towing Air Streams but not for sucking the doors off Chevys. What was significant about the 390 Mustang (which looked street-snazzy in GT form), was that it laid the groundwork for a powerful generation of Mustangs that would arrive it 1968, led by the 428 Cobra Jet. After watching a stock 1968 428 CJ Mustang click off the quarter-mile in 13.56 seconds at 106.6 mph (fully two seconds faster than the 390), Hot Rod would be moved to exclaim, “It is probably the fastest regular production sedan ever built.”

From there, Ford would build a line of muscular Mustangs from 428 Mach 1s to Boss 429s that would take on the big block Chevys, 455 Trans Ams and the dreaded Plymouth Hemis. These powerful ponies would acquit themselves well in battle, both on the street and the track. That would be several years after Ford’s “Total Performance” program first mated the Mustang with the 390 back in 1967.

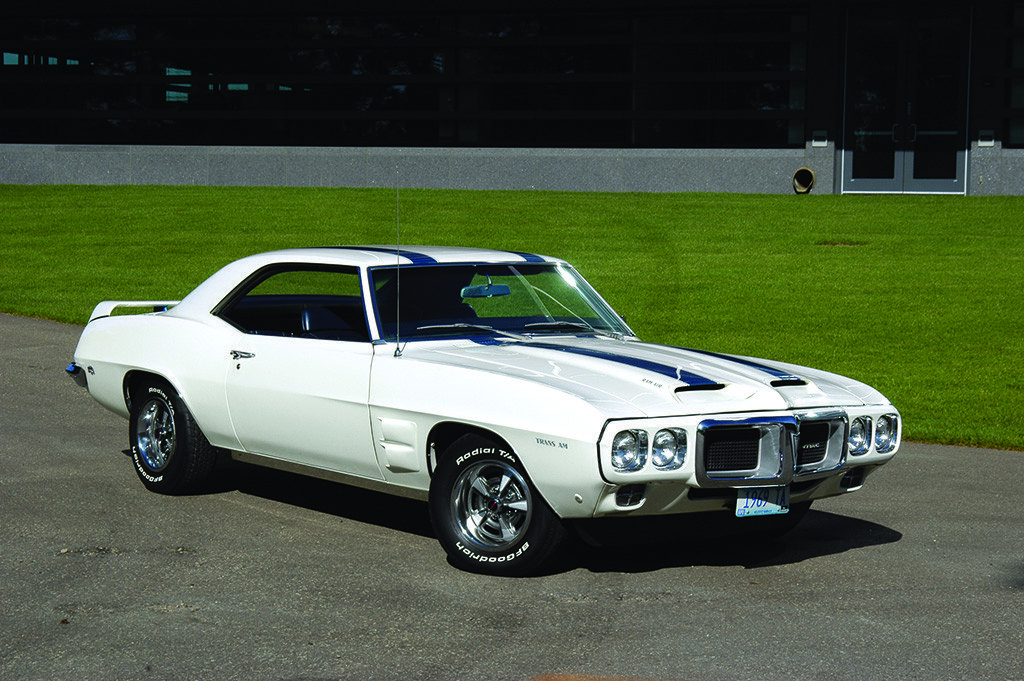

1969 Pontiac Trans Am

From the time he was Chief Engineer until he was appointed Pontiac’s General Manager in 1965, John Z. DeLorean wanted to build a two-seat sports car. Not to compete against the up-scale Corvette, but to take on the Mustang. Time and again he took his proposals and clays to GM management, and time and again he was shot down. So when he learned in 1966 that he would be getting a version of GM’s Mustang fighter six months after Chevrolet would release their version, he wasn’t completely gung ho on the assignment.

That extra six months allowed Pontiac to improve the GM F-car. While the fundamental sheet metal was the same, the Firebird shared little else with the Camaro. Pontiac was able to refine the brakes and suspension and with its 215-horsepower overhead cam six engine, the Firebird was as close to a European sports sedan as Detroit could make. Along with two OHC sixes, Pontiac offered two 326 cubic inch V8s and a 400 that produced 325 horsepower.

The prize each pony car manufacturer eyed was the Trans-Am series, and Pontiac was ready to enter the fray against Chevy and Ford. What handcuffed Pontiac was its lack of a small displacement engine. While they could have destroked their 350 cubic inch V8, it couldn’t produce the kind of power needed for racing. An 18-month crash program to build a 303 cubic inch engine with special round port heads resulted in frustration, and Pontiac ended up never being a contender in the Trans-Am race series.

That didn’t mean they couldn’t cash in on the SCCA’s name. Pontiac developed an option for the 1969 Firebird that used the series’ name and agreed to pay the SCCA a $5 per car royalty for every Trans Am sold. A total of 697 Trans Ams were built that first year, either with the standard 400 cubic inch Ram Air III or the optional Ram Air IV. What made the 1969 Trans Am significant to pony car history wasn’t its first year of production, but how the nameplate successfully lasted for an additional 33 years, especially through the tough mid- to late 1970s. Pontiac sold hundreds of thousands of Trans Ams and, until the end of 1982 it was the Corvette’s only competitor. It may have never raced, but thanks to that $5 spiff, the Pontiac Trans Am made a ton of money for the Sports Car Club of America.

1970 AAR Plymouth ’Cuda

Even if Plymouth hadn’t chosen to go racing in the Trans Am series, the AAR ’Cuda would still have been one of the most memorable muscle/pony cars of 1970. Inspired by the All American Racing team of Dan Gurney, the AAR ’Cuda was a preponderance of strobe stripes, matte black hood, side pipes and a 340 engine that boasted a trio of Holley two barrel carburetors parked on an Edelbrock intake manifold, right from the factory.

Rated at 290 horsepower, the AAR ’Cuda’s 340 engine used the same block and heads as the race engine, however it was much calmer than the race version, which produced over 460 horsepower. Road tests of the day indicate the AAR ’Cuda was an excellent road car. The usually unrepentant three-deuce carburetor setup was smooth throughout the rpm range. That was unusual since multiple carburetion was usually either lethargic under low acceleration or neck snapping when the wood was put to it with no in between.

The Barracuda’s redesign in 1970 made it wider, lower and longer, and finally in a class with the Camaro, Firebird, and Mustang. While Dan Gurney and Swede Savage didn’t fare well in racing, the AAR ’Cuda didn’t do badly in the showroom selling 2,727 copies (the SCCA homologation rule was 2,500). When Plymouth chose to drop out of the Trans-Am in 1971, the AAR ’Cuda was withdrawn.

Today, the AAR ’Cuda is more a testament of how Detroit could dress up a performance car with what many young drivers were doing on the street. Blacked out hoods, side exhausts and multiple carburetion were popular at Drive-In parking lots where high schoolers congregated with their cars on Saturday nights. Not many 18 year olds actually could buy an AAR ’Cuda, but it was a sure bet they had posters hanging on their bedroom walls. Did that translate into more Barracuda sales? Probably not, but it was all about the image, baby, and Plymouth had that in spades.

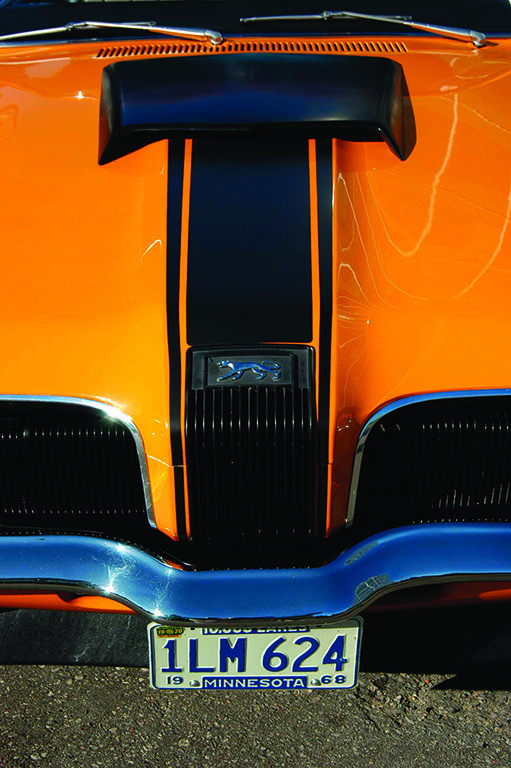

1970 Mercury Cougar Eliminator

When Ford chose to give a pony car to the Lincoln/Mercury division, it was a foregone conclusion that it would be accorded a posh interior, soft ride, and luxury looks. The resulting 1967 Cougar was all that and more. It featured disappearing headlamps, a 200-horsepower 289 cubic inch engine and sequential lighting rear tail lamps. The XR-7 option included a 390 cubic inch engine, four speed transmission and upgraded interior.

Even Lincoln/Mercury couldn’t resist the temptation to jump into the muscle/pony car market in 1969, even though the Cougar had no performance heritage to speak off. In what has to be one of the most stilted  advertising phrases of the ’60s, Mercury launched their “Streep Scene.” Streep being a combination of strip and street, see? To ballyhoo their drag racing efforts, Mercury commissioned “Dyno” Don Nicholson to campaign a tube-framed Cougar funny car named “Eliminator.”

advertising phrases of the ’60s, Mercury launched their “Streep Scene.” Streep being a combination of strip and street, see? To ballyhoo their drag racing efforts, Mercury commissioned “Dyno” Don Nicholson to campaign a tube-framed Cougar funny car named “Eliminator.”

That lead to a high performance street version that for 1970 featured a standard 300-horsepower, 351 cubic inch engine, rear deck wing, matte black hood scoop with an optional bold black strip running from the grille to the scoop, and black body stripes that extended along the upper belt line. Also optional was the 335-horsepower, 428 Cobra Jet with Ram Air as well as the “Drag Pack,” which featured an engine oil cooler and 4.30:1 Detroit Locker differential. Even the Boss 302 engine was on the order sheet.

While Mercury didn’t fail to install the necessary hardware to make the Eliminator run like a performance pony car and look like a performance pony car, what they couldn’t do was bolt an image onto the Cougar. It was virtually impossible to sell the youth market on the premise that their father’s Mercury was hotter than a Mustang, Camaro or Firebird. That was the kiss of death, and after 2,267 were sold in 1970, the Eliminator and the “Streep Scene” were swept away. It was a textbook lesson in how Mercury failed to understand it took more than a flashy name to establish credibility with a young, but very critical market.

1970 Dodge Hemi Challenger

After watching from the sidelines since 1965, Dodge was finally in the pony car fracas with their new 1970 Challenger. They had chosen to take a pass on Chrysler’s offer for a Barracuda version in 1966, instead introducing the mid-sized Charger. And while the Charger hit its stride beginning with the beautifully redesigned 1968 model, Dodge still chomped at the bit for a pony car. The Challenger may have been the last pony car nameplate in the marketplace, and it couldn’t match the Camaro or Mustang in sales volume, but it still managed to outsell its Barracuda sibling by almost 50 percent.

The Challenger was actually larger than the Barracuda, with a two-inch longer wheelbase, and shared little with its Plymouth cousin. The Challenger had a complete line of nine available engines, from the indestructible Slant Six all the way up to the King Kong of all street engines, the 426 cubic inch Hemi. Named for the design of its hemispherical combustion chamber, the Hemi was fundamentally a race engine detuned for the street. With dual four-barrel carburetors, solid lifter valve train and 425 horsepower on tap, the Hemi was finicky to run on the street. But when in full song, the Hemi could propel the Challenger down the quarter-mile in mid 13 second elapsed times. Not bad for a 3,800 pound pony car.

Inside, the Challenger’s interior was driver oriented, with three large, round pods that, when ordered, contained optional gauges including tachometer. The transmission of choice for Dodge fans was the bullet proof 727 TorqueFlite three-speed automatic, which had earned its bones with performance fans in the early days of Super Stock racing. Those who chose to shift for themselves had to handle the awkward “Pistol Grip” shifter and lumbering A-833 manual four-speed. Most chose the TorqueFlite.

While the 440 cubic inch Six-Pack V8 with its 390 horsepower could beat the Hemi like a drum, on the street, there was no other engine with the image or the heritage. From super speedway NASCAR racing to wheel-standing NHRA competition, the Hemi was the undisputed heavyweight champ. Just 356 customers chose to throw down the extra $648 for a Hemi in the R/T model ($779 in any other Challenger). It was worth every penny just to drive a legend in its own time.

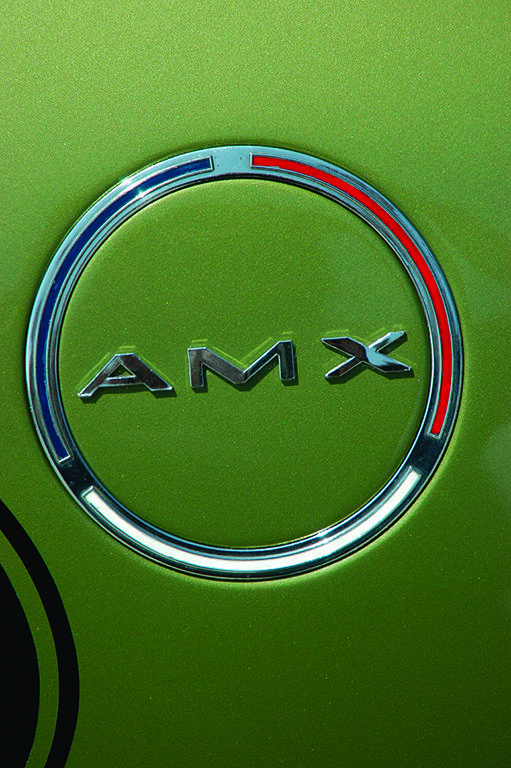

1970 AMC AMX

All through the 1960s and early 1970s, American Motors Corporation had to fight for a very small slice of the American automotive market. “If you had to compete with GM, Ford, and Chrysler,” AMC once asked in an advertisement, “what would you do?” To capture their small share, AMC had to develop alternative choices for the consumer. When AMC discovered performance and pony cars in 1968, they shed their old staid image. Car & Driver thought “American Motors had stopped holding its pants up with both belt and suspenders.”

When the Javelin was released on September 26, 1967, AMC had done their homework well and built a car that met all the standard pony car criteria – long hood/short deck, 2+2 cockpit and plenty of options. In its first year, the Javelin won the praises of road testers and outsold the Barracuda. It was a credible entry into the market, however, AMC had a trump card.

That ace in the hole was called the AMX, and it was the alternative card that AMC played not against the Mustang or the Camaro, but the Corvette. Was it a sports car or was it a two-seat sporty car? Or was it a long hood/short deck pony car that was honest enough to admit what all the others wouldn’t, and that was the idea of a real rear seat in a pony car was a wicked canard?

The AMX cost two grand less than the Corvette, and by 1970 had built a solid reputation with a small cadre of performance enthusiasts. In its final iteration, the 1970 AMX was the best of the run, with a 360 cubic inch engine standard (the 390 was optional), functional Ram Air, redesigned front  suspension and vented front brakes. The front end was face lifted and extended two inches. Inside, the cockpit was redone, with a flat, wood-grained instrument panel reminiscent of an English sports car. Large nacelles placed the instruments clearly in front of the driver, and a rim blow steering wheel and high-back bucket seats were standard. AMC minted 4,116 AMXs in 1970 and then bowed out of the two-seater market.

suspension and vented front brakes. The front end was face lifted and extended two inches. Inside, the cockpit was redone, with a flat, wood-grained instrument panel reminiscent of an English sports car. Large nacelles placed the instruments clearly in front of the driver, and a rim blow steering wheel and high-back bucket seats were standard. AMC minted 4,116 AMXs in 1970 and then bowed out of the two-seater market.

As an alternative to the Corvette, the AMX did what it was intended to do, and did it briskly. In their December 1969 issue, Motor Trend put a 390 AMX to the test and netted 0-60 acceleration in 6.56 seconds and recorded a quarter-mile in 14.68/92 mph. Those times placed it clearly in Corvette territory, or was it Camaro territory? Or better yet, AMX territory.

Text and Photography by Paul Zazarine

© Car Collector magazine, LLC.

(Click for more Car Collector Magazine articles)

Originally appeared in the August 2007 issue

If you have an American muscle car or another collectible you’d like to insure with us, let us show you how we are more than just another collector vehicle insurance company. We want to protect your passion! Click below for an online quote, or give us a call at 800.678.5173.

Leave A Comment