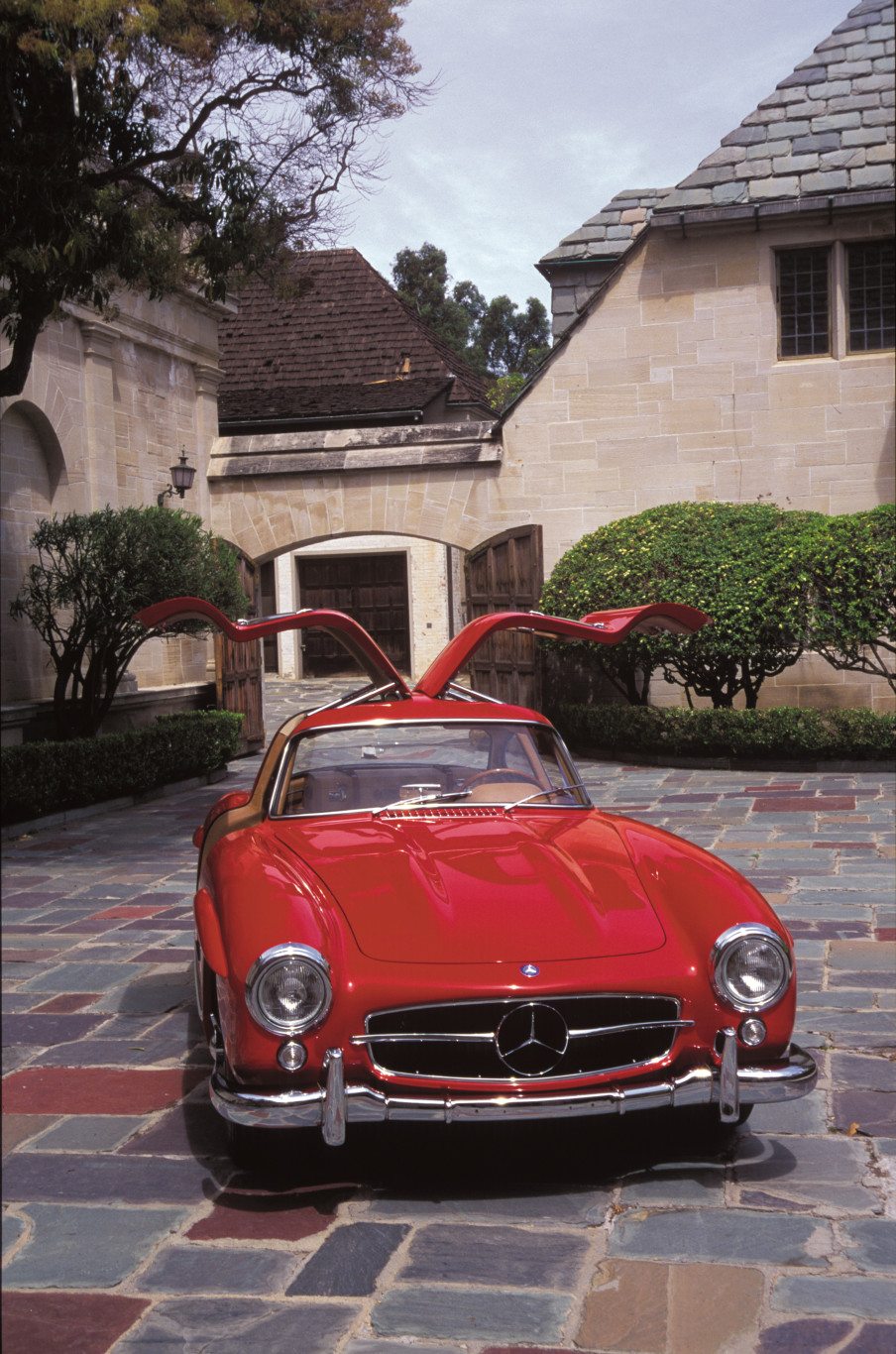

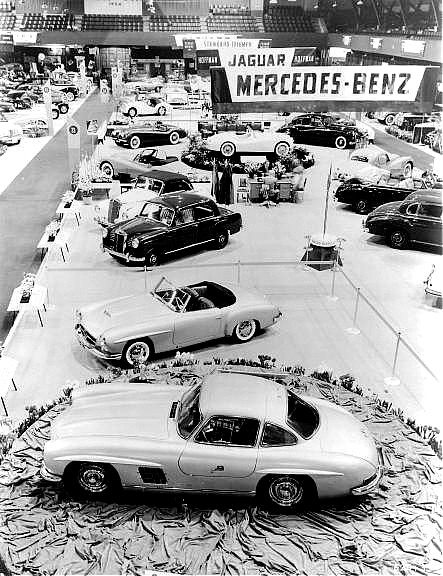

At the opening of the annual New York International Motor Sports Show on February 6, 1954, Daimler-Benz did something quite unexpected; the renowned German automaker introduced the 300 SL Gullwing coupe and 190 SL roadster. What so distinguished this event was that the cars had not yet been introduced in Germany! This unprecedented world debut was orchestrated by Max Hoffman, upon whose insistence Daimler-Benz had built the 190 SL and production version of the championship 300 SL racecars. And while New York in the throes of winter might have seemed an unlikely place to debut a pair of sports cars, Manhattan was also the home of Hoffman Motors, the Park Avenue dealership that had established the German automotive industry in America after World War II.

It seems there is hardly a postwar European sports car story that can be told that does not in some way involve Max Hoffman. Born in Vienna, Austria, he was an avid sportsman who began an amateur racing career in the 1920s riding DKW and AJS motorcycles. He finally graduated to sports cars and continued to race professionally until 1934, when at age 30, he decided to retire and step from the cockpit to the sales floor, becoming a dealer and importer in Austria for Auburn, Cord, Duesenberg, Lancia, Pontiac and Vauxhall. He later added such renowned marques as Rolls-Royce, Bentley, Alfa Romeo, Talbot, Delahaye, Volvo (the first importer in Europe) and Hotchkiss to the lines marketed through Hoffmann & Huppert. (In America, Hoffman dropped the second “n” from his surname and occasionally used his entire first name, Maximilian. As he once noted, “It was more fitting in New York for a purveyor of exotic motorcars.”)

Hitler’s rise to power and the stranglehold the Third Reich had on Germany and Austria in the late 1930s deeply concerned Hoffman, who could find no common ground with the Nazi Party or their policies. Fearing the worst, he moved his business to Paris, which lasted until France declared war on Germany, prompting him to pack his bags and book passage on the first ocean liner headed for New York. After December 7, 1941, even that proved to be a problem. With America entering the war the U.S. automobile industry seemed to vanish almost overnight, and there was certainly little need for an importer of German automobiles in the United States! To make ends meet Hoffman launched a new venture, manufacturing costume jewelry made out of metal plated plastic. Like most everything Max touched, this too turned to gold, or rather gold plate. In his first week of business he booked $5,000 in orders!

By the time the war was over, New York City had become Max’s home, and while the jewelry business had been a financial windfall in the 1940s, he longed to get back to his automotive roots. He had come to this country with the intention of importing cars from Europe and with the profits from his jewelry business he was able to open the Hoffman Motor Car Company with a spectacular showroom located in the heart of Manhattan on the corner of Park Avenue and 59th Street.

America in the postwar era was an incredible place to be. Soldiers were returning home, industry was booming, and Americans were car starved. To quell those pangs of automotive hunger, beginning in 1947 Max Hoffman dished up some of the finest imported cars built in Europe. Initially he sold French Delahayes, Italian Lancias, and a handful of British makes, including the stunning new Jaguar XK120, one of his personal favorites. By the early 1950s he had become the sole United States importer and distributor for both Mercedes-Benz and BMW, and was soon to become the principal dealer for the Volkswagen, which made its U.S. debut on July 17, 1950, at Hoffman Motors.

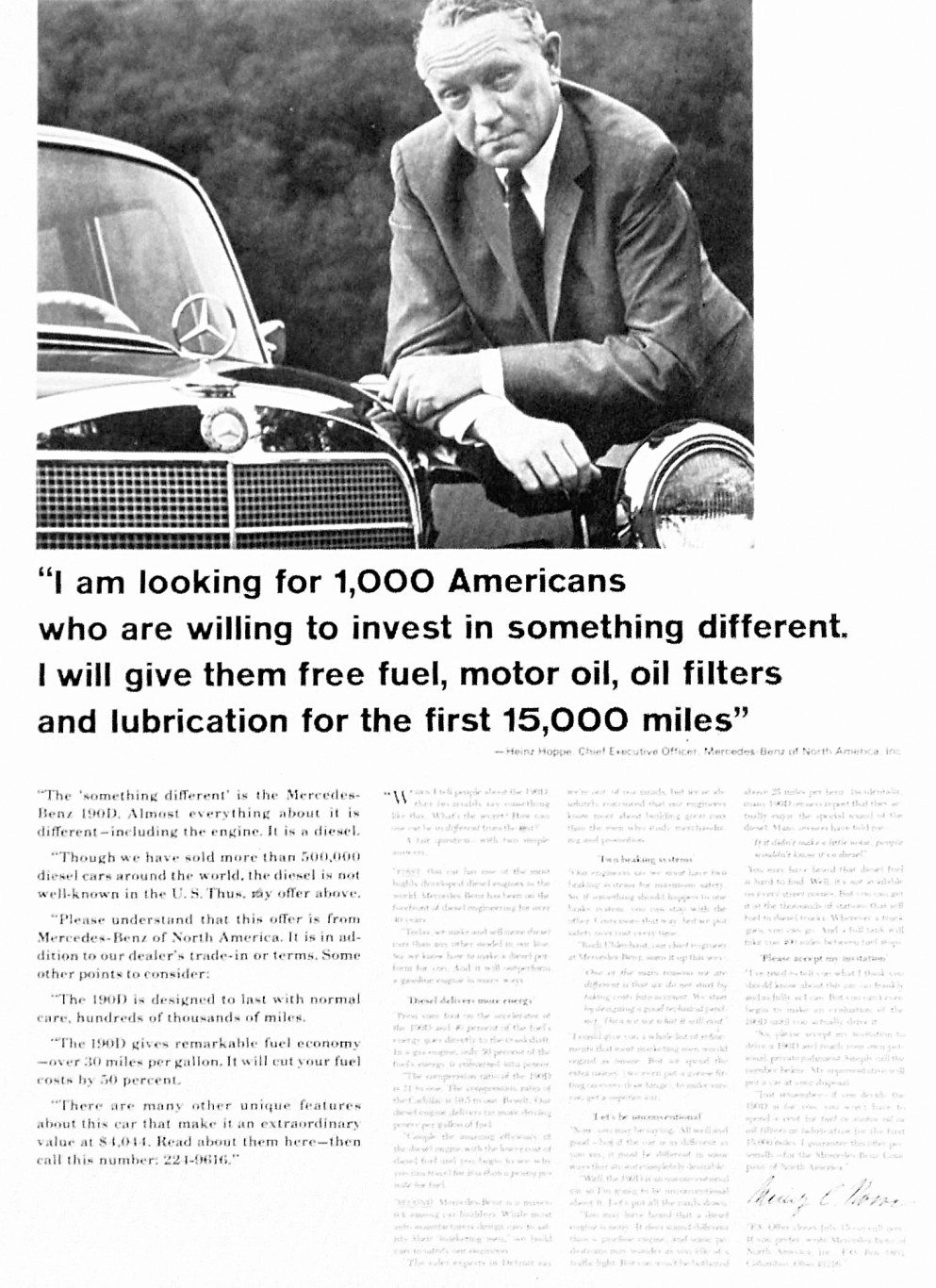

As an automaker, Daimler-Benz AG had set its sights on the American market around the same time the 300 SL was introduced in New York, with the intent of establishing its own marketing network and eliminating Hoffman and his New York and Los Angeles dealerships, which also sold competitive models from BMW, Porsche, Jaguar and Alfa Romeo. The plan was set into motion after the 300 SL’s debut, and in the fall of 1954 Daimler-Benz hired an English-speaking Austrian businessman named Heinz Hoppe, who was sent to the United States to lay the groundwork. By 1957 Hoffman was out, but his replacement was perhaps even more problematic.

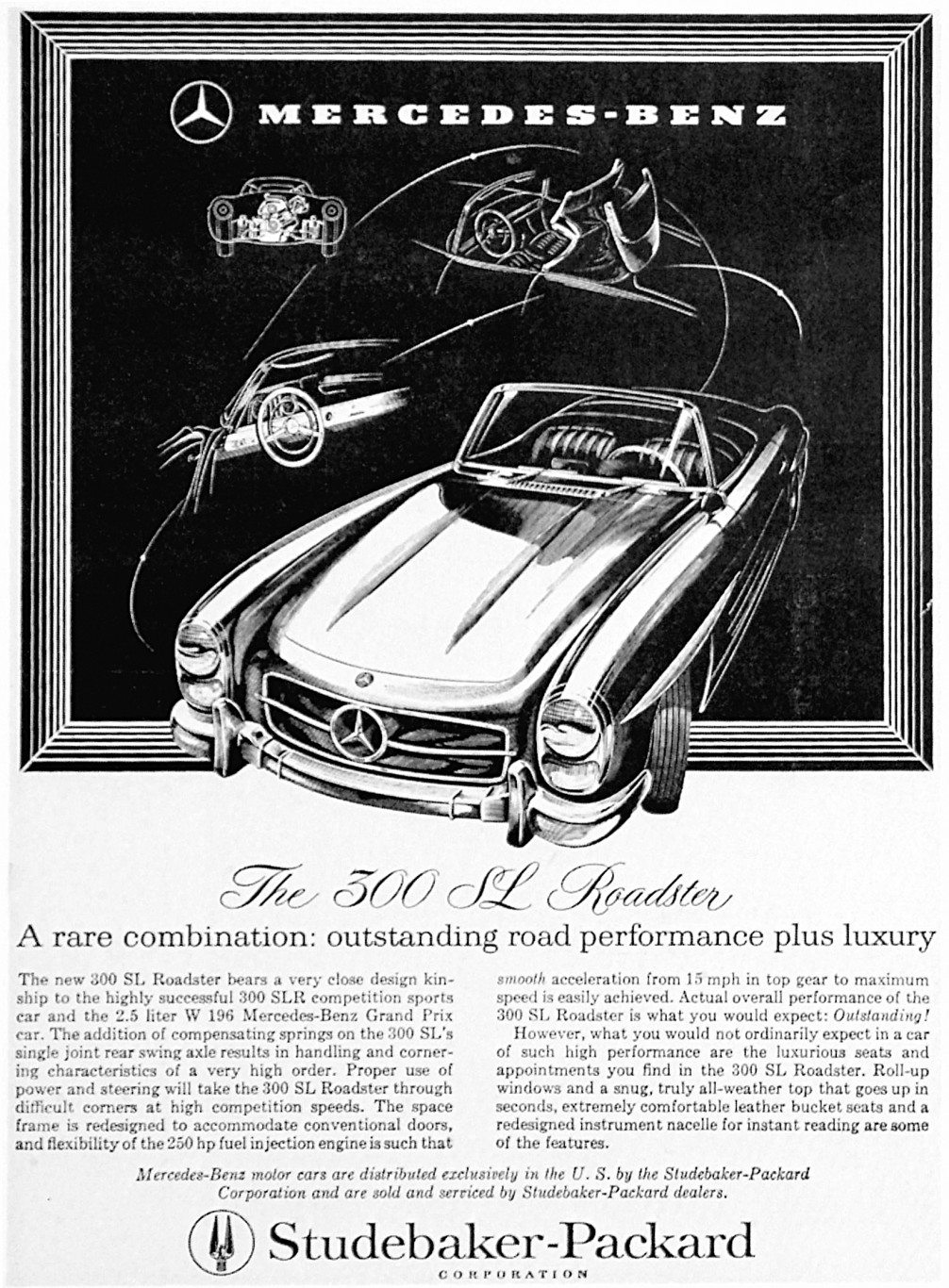

Mercedes-Benz began its American venture with an unlikely alliance between Daimler-Benz AG and a struggling automaker in need of a way to boost its declining image—Studebaker-Packard. What made Studebaker-Packard attractive was its acquisition by aviation giant Curtiss-Wright in 1956. This appealed to Daimler-Benz management, since they had wished to find an aircraft engine builder as a U.S. partner. The agreement, drawn up between the two companies in 1957 by Hoppe’s superior in Stuttgart, Carl Giese, instantly gave Mercedes-Benz a distribution network of 2,500 dealers. Unfortunately, as Hoppe had feared, Studebaker-Packard salesmen hadn’t a clue how to sell foreign cars, or how to handle the temperamental nature of customers interested in such unusual automobiles. Giese’s “marriage made in heaven” was slowly heading toward the nether regions but Hoppe managed to keep it working for nearly a decade, establishing Mercedes-Benz Sales Inc. in August 1958, as a subsidiary of Studebaker-Packard.

To say the relationship between Daimler-Benz and Studebaker-Packard was rocky would be a kind assessment. Curtiss-Wright had hoped the alliance with Daimler-Benz would prop up faltering Studebaker and Packard sales. It did not. To make matters worse, the marketing people in Germany had expected Studebaker-Packard to establish Mercedes-Benz as an import flagship model line. That too, failed to materialize and Daimler-Benz further complicated the situation by wanting S-P dealers to also sell the little two-stroke Auto Union cars. Even one that looked like a 1957 Thunderbird failed to impress American buyers. (After the war Daimler-Benz had purchased Auto Union, one of its biggest motorsports competitors back in the 1930s. Auto Union was manufacturing small cars with 2-stroke motors. Selling a car to Americans that required mixing oil with gasoline was truly the definition of foreign.)

When the South Bend automaker finally folded its tents in 1964 and moved what remained of its operations to Canada, Hoppe convinced the Daimler-Benz board to act quickly and separate itself from the ill-fated company through a $3.75 million buyout of the contract binding Mercedes to Studebaker-Packard. Hoppe orchestrated the deal and then established Mercedes-Benz of North America as a separate company in April 1965, selecting the best of the former Studebaker-Packard dealers to be the first Mercedes-Benz dealerships in the United States. By this time Giese had been replaced by Günther Wiesenthan who was appointed president of MBNA. However, Wiesenthan remained in Germany with Hoppe, as executive vice president, running the company from the U.S.

The first home office for MBNA was in Fort Lee, New Jersey, just across the Hudson River from Manhattan where it had all begun with Max Hoffman almost 20 years earlier. Under Hoppe’s management MBNA established a dealer network, vehicle preparation centers, parts depots and training schools, making the American sales and marketing division almost totally self sufficient.

In 1970, Hoppe returned to Germany and took a seat on the management board, helping guide the expansion of Daimler-Benz across Europe in the same way he established Mercedes-Benz in America. Hoppe was ultimately responsible for Daimler-Benz subsidiaries in Great Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Italy and Austria. But it had all begun in America.

by Dennis Adler

(Photos by the Author and DaimlerChrysler Archives)

© Car Collector Magazine, LLC.

(Click for more Car Collector Magazine articles)

Originally appeared in the March 2005 issue

If you have an early model Daimler-Benz or another collectible you’d like to insure with us, let us show you how we are more than just another collector vehicle insurance company. We want to protect your passion! Click below for an online quote, or give us a call at 800.678.5173.

Leave A Comment