This is the tale of two Mustangs. Both were called “Boss”. Both were built to homologate racing engines. Both became legends among Mustang lovers and muscle car aficionados, but that’s where the similarity ends, because each was totally different from the other.

In the case of the Boss 302, it was not only built to homologate the 302 for racing in the SCCA’s Trans-Am series, but to take the Mustang/Camaro battle that raged on the road course to the street. The Trans-Am series had quickly become not only a manufacturer’s showcase for their pony cars, but a door banging, fender crunching series that wowed the growing numbers of spectators. Chevrolet’s Z/28 had been built in 1967 to legalize Chevy’s special small block for the Trans-Am. Ford had watched the Z/28’s sales climb from 602 in 1967 to 7,199 in 1968, and there wasn’t a Mustang to match it.

The catalyst for change came in the form of Semon “Bunkie” Knudsen. Knudsen had risen through the ranks at GM, moving Detroit Diesel to Pontiac in 1956, then up to Chevrolet in 1961, and finally in 1965, to GM’s executive offices on the 14th floor of the GM Building. When Ed Cole was tapped to be the corporation’s next president (a position Knudsen felt he deserved instead of Cole), Knudsen accepted an offer from Henry Ford II to become president of Ford. Henry Ford II’s products weren’t as competitive with GM as he wanted, and he felt Knudsen could put some excitement back in the blue oval brands.

Knudsen was aware of Ford’s lack of spark in the product lineup, especially the Mustang. “Ford had the Mustang,” Knudsen would recall some years later to author Donald Farr,”which was certainly a good-looking automobile. There was nothing wrong with it, but there was a tremendous amount of people out there who wanted good-looking automobiles with performance. If a car looks like its going fast and it doesn’t go fast, people get turned off. I think if you have a performance car and it looks like a pretty sleek automobile, then you should give the sports-minded fellow—the car buff—the opportunity to buy a high performance automobile.”

The timing for Knudsen’s arrival couldn’t have been better for Mustang. After a disastrous year in Trans-Am with the unreliable 1968 Tunnel Port 302 engine, Ford engineers had hit upon using a new canted cylinder head design that inclined the valves towards the ports and improved flow. Their “semi-hemi” poly angle valve placement made power across the mid and higher rpm ranges. These “Cleveland” heads (named for the plant) were initially designed for the upcoming 351 engine, but bolted to the 302 block just as easily. With huge 2.23 inch intake and 1.71 inch exhaust valves, and free flowing ports, the heads moved a copious amount of air, but not too much to cancel out the 302 block’s volumetric flow. This resulted in slightly sluggish performance below 3,000 rpm, but when the engine wound up, the power band came on fast and furious right up to 7,000 rpm.

The rest of the 302 was comprised of a high nickel alloy block with a thicker deck, and cylinder walls with a bore diameter of 4.00 inches. The cross-drilled, high strength steel forged crankshaft was retained by stronger four-bolt main caps. The 10.50:1 aluminum pistons rode on heavy, high strength steel forged rods with a 3.00 stroke designed for high rpm usage. Under the pent-roof valve covers was a solid lifter valve train with enormous 1.73:1 rockers. An aluminum high-rise intake manifold and 750 cfm Holley carburetor were also included. A dual point ignition supplied the spark. In race form for SCCA Trans-Am competition, the engine could be built to produce a reliable 450 horsepower. For the street, Ford played the Z/28’s game and underrated the 302 at 290 horsepower at 5,800 rpm (it produced more like 350 horsepower). The standard (and only) transmission was the Ford “Toploader” close-ratio four-speed manual with 3.50 rear axle. Car & Driver would pilot a Boss 302 through the quarter-mile at 14.57/97.57 mph and accelerate 0- 60 in six seconds flat.

While the engine development was underway, Ford commissioned Kar Kraft of Brighton, Michigan, to engineer a suspension for the Boss 302. Kar Kraft had a long and successful association with Ford building the GT40s for LeMans racing. Knudsen made it clear that he wanted “the best handling street car available on the American market.” With that mandate, Kar Kraft set about reworking the Mustang’s basic suspension geometry. Between computer analysis and plenty of track testing, stiffer springs, fatter stabilizer diameters, and shock absorber valving were all tested based on wide 15 x 7-inch wheels on F60 tires (the front fender wheel openings had to be cut and rolled under to clear the tires). The increased tire adhesion created new problems in the area of chassis and steering component stress. The rear shock placements were staggered to handle the increased lateral loads. Front spindles, shock towers, and upper control arm mounts were strained beyond their design limits. Tower supports and heavier duty spindles were dialed in to alleviate the problems. A ½ inch rear stabilizer bar wasn’t approved until the 1970 models were released. Quick ratio steering and power front disc brakes with Boss 302-specfic 11.3 inch rotors with 10 inch rear drums were standard.

It didn’t take Knudsen long to realize he had a real winner here. Dropping this new 302 into a tricked up Mustang and releasing it on the street was exactly what Ford needed to buck up their pony car’s sagging sales and image. Knudsen also knew the car needed the “Wow!” factor. That was solved by the entry of designer Larry Shinoda. Shinoda had been with GM, and was responsible for the design of the 1963 Corvette, the 1968 Corvette, and the styling for the 1967 Z/28. He had worked closely with Knudsen, and bringing Shinoda over to Ford would enable him to put more visual appeal in to the products.

Shinoda went right to work. He wanted to set this special Mustang apart from standard production versions. He started by removing the pony emblems on the C pillars and the false air scoops. He added the spectacular “Sports Slats”, (a louvered cover over the Mustang’s large rear window). It was similar to the 1962 Monza Spider show car that he had designed. Ford management nearly went apoplectic when they saw Shinoda’s proposal, but approved it when they realized the slats still provided adequate rear vision. They were so popular that they became an over the counter accessory for any fastback 1969 Mustang. Pennsylvania disagreed however, and outlawed them in the state.

Shinoda was more than a designer, he was also a race fan, and understood the need for aerodynamic enhancements. He had designed the spoilers for the Z/28, and drew up a handsome and efficient front “shovel” style spoiler and a rear wing for this special Mustang (the rear wing was optional, but over 80 percent were so equipped). Along with a bold body side stripe package, he also painted the front lamp surrounds, the cowl, and the hood Matte Black. He coined the name The Boss 302 for Ford’s Z/28 fighter. Ford had wanted to name it Trans Am, but GM had already snatched it under license from the SCCA. Another choice was “SR-2”, but in the end, the Boss 302 moniker was approved.

Just 14 months after Knudsen had arrived at Ford, the first Boss 302s began rolling off the Dearborn Assembly Plant’s line on April 17, 1969. Production ramped up to hit the magic 1,000 mark for homologation, which was achieved less than a month later on May 11. The total 1969 Boss 302 production came to 1,628.The Boss wasn’t cheap; the base price was $3,685. Only four colors were offered: Bright Yellow, Calypso Coral, Wimbledon White, and Acapulco Blue.

Just before the 1970 models were to be released, Henry Ford II fired Knudsen. It took Lee Iacocca less than two years to torpedo Knudsen and get him out of Ford, paving the way for Iacocca to run the company himself.

The 1970 Boss 302 survived both Knudsen and Shinoda, who was shown the door two weeks after Knudsen’s departure. The Boss 302 shared the Mustang line’s new front end that featured dual headlamps within the grille, and coves with horizontal slots where the second set of headlamps had resided in 1969. The front shovel spoiler was revised, with more rounded ends and a different texture. Around back, the tail lamp panel was blacked out, as was the decklid. The fiberglass rear wing was heavier than the previous unit, requiring a prop rod to keep the decklid open.

The most dramatic change to the Boss 302 was the hood. Gone was the massive Matte Black treatment, replaced by a flat black center stripe with narrower stripes on each side that went out to the fenders at right angles and wrapped down to mid fender before turning rearward and running the length of the lower beltline to the rear bumper. Exterior color choices were expanded to almost the entire Mustang palate. Interiors were relatively unchanged, with the exception of new upholstery trim and high back bucket seats.

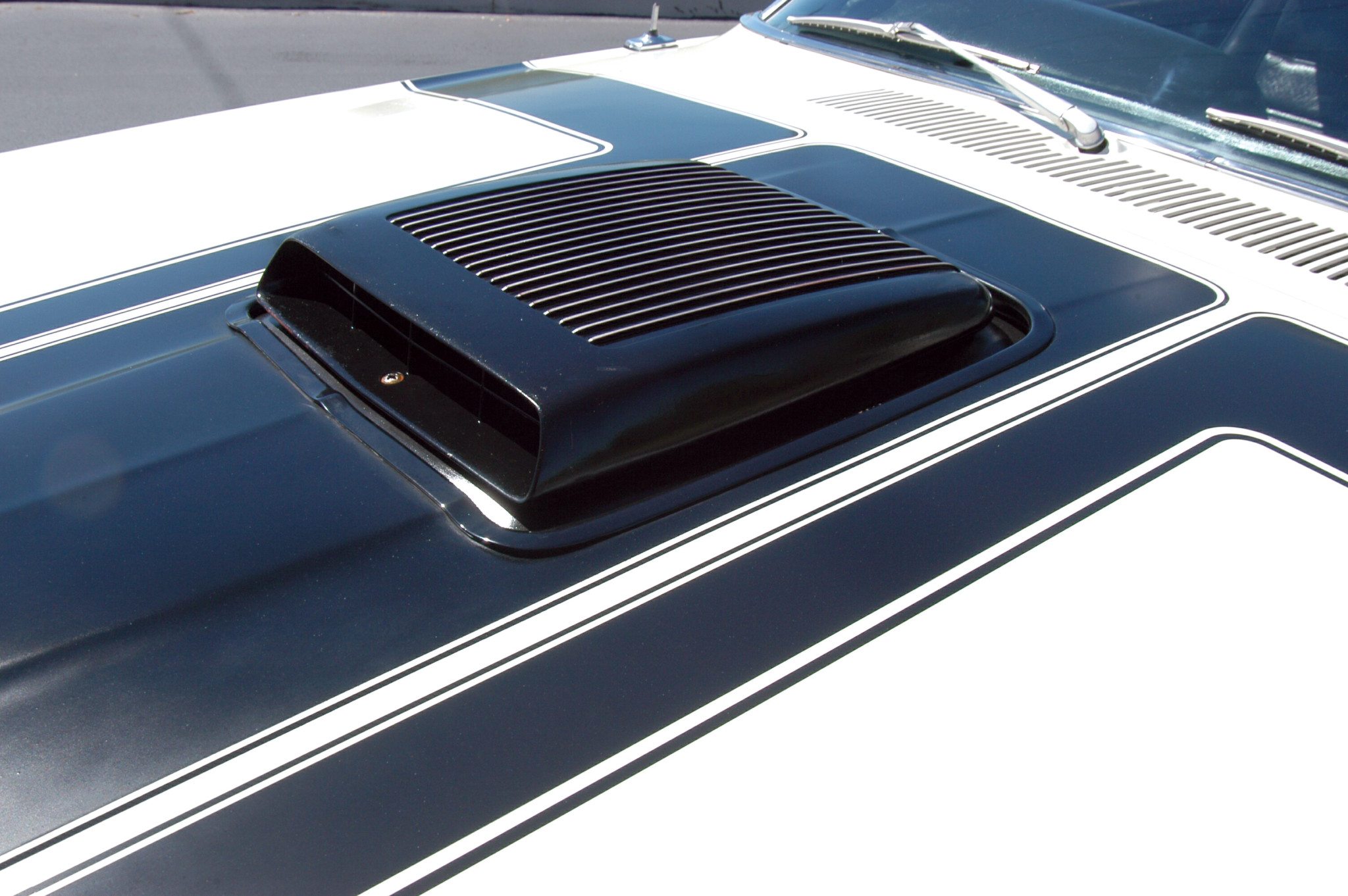

Poking out of that newly styled hood was an optional “shaker” ram air scoop. A hole was cut in the hood and a scoop assembly mounted atop the air cleaner rose through it. The scoop would open via an engine-operated vacuum valve, allowing the engine to suck in colder outside air. The major changes were a revision of the front hang-on hardware and pulleys, and finned valve covers. Intake valve diameter was reduced .04 inches and the cranks were no longer cross-drilled. The Toploader four-speed and 3.50 rear continued as the standard powertrain. To stir the close ratio transmission, Ford chose to use a Hurst Competition shifter with “T” handle.

For 1970, the SCCA homologation rules were changed for Trans-Am cars; manufacturers were required to build 7,000 production versions. Ford met that minimum by producing 7,013 Boss 302s in 1970. The SCCA Trans-Am would wind down after 1970 as manufacturers dropped out of the series, but in the two years when Ford’s Boss 302 and Chevrolet’s Z/28 battled on the road course, it made for some of the most intense and exciting racing in America.

There was another Boss Mustang roaming the streets in 1969 and 1970, however this one wasn’t involved in Trans-Am racing. While Kar Kraft was developing the Boss 302 package, they were also working on another package, which would eventually be named the Boss 429.

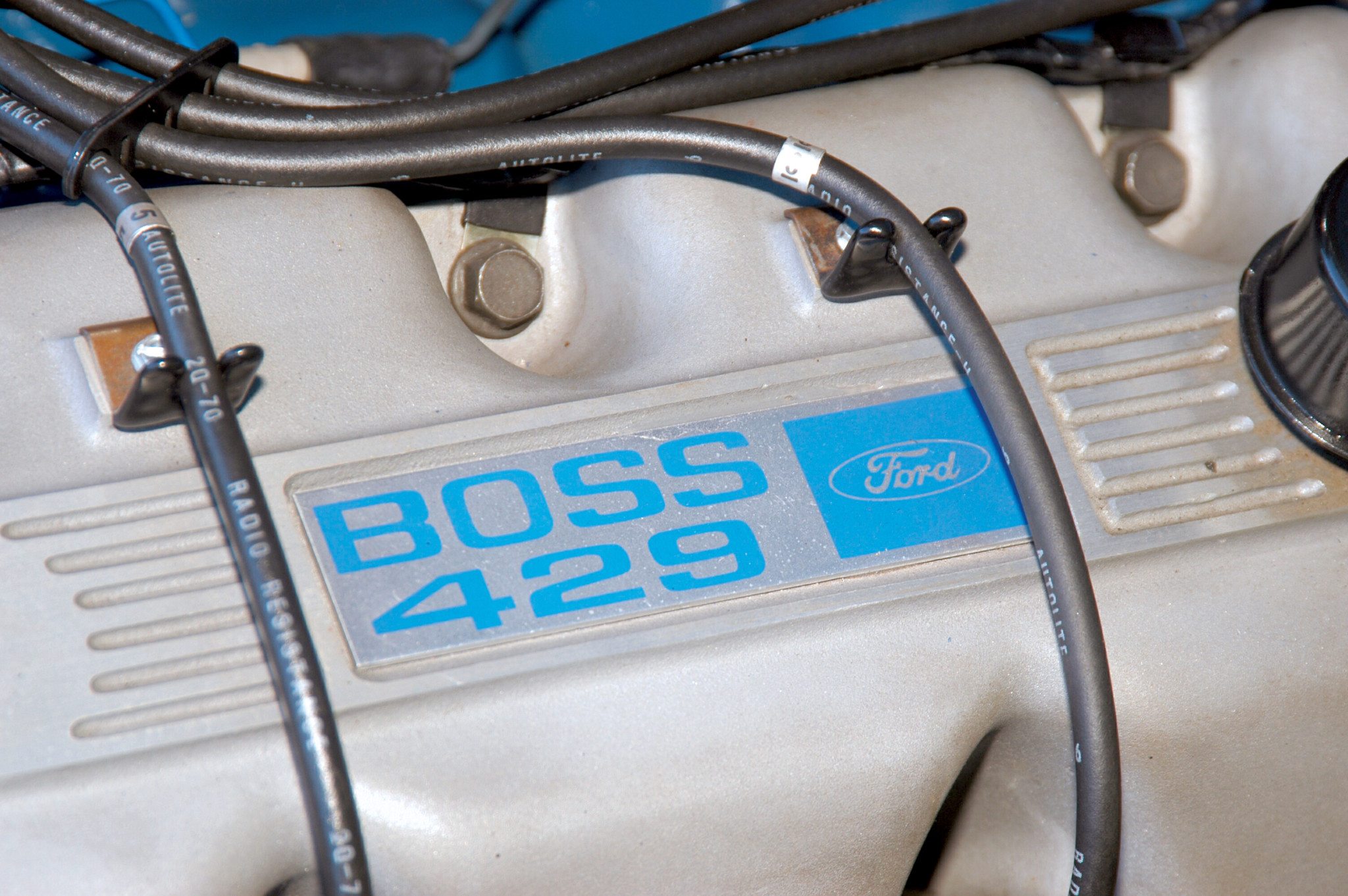

The Boss 429 was produced for one reason, to homologate Ford’s “semi-hemi” NASCAR engine for competition. Ford was still struggling to compete with Chrysler’s 426 Hemi, and the new “Blue Crescent” 429 had all the earmarks of taking the game right back to Dodge and Plymouth. Based on a beefed up version of the production 429 block, the Boss 429 had four bolt mains, forged steel crank, and forged steel connecting rods. What set the engine apart, and made it such a competitor for the 426, was its aluminum cylinder heads that featured a “crescent” shaped combustion chamber and huge 2.3 inch intake valves. Another unique feature was the “dry-deck” method that replaced the use of head gaskets. Instead, “O” rings were installed to seal the cylinders, and the water and oil passages. Riding on top was a Holley four-barrel carburetor, parked on an aluminum intake manifold. For drivability, a hydraulic valvetrain was employed. In full street dress, air cleaner and emissions equipment in place, and closed exhaust, the Boss 429 produced 375 horsepower. On the NASCAR track in race form, the engine put out nearly double that amount.

The Mustang would never compete in a NASCAR race, but it could carry the 429 to make it legal for racing. While the Torino would have been the logical choice for the 429, Knudsen, again, wanted to give the Mustang an extra pump on the performance meter. Interestingly enough, a well-tuned 335 horsepower 428 Cobra Jet Mustang could kick a stock Boss 429 to the curb. Magazine tests reveal the 428 CJ ran the quarter mile as much as .5 seconds faster.

Kar Kraft had their engineering hands full trying to drop the King Kong 429 between the Mustang’s narrow shock towers. Considering the low production numbers (859 in 1969 and 500 in 1970), considerable money went into these conversions. Ford would ship partially completed SportsRoof Mustangs that were built for the 428 Super Cobra Jet engine to Kar Kraft. These cars were already equipped with heavy-duty suspensions. Kar Kraft would add the staggered shocks, ¾ inch rear stabilizer bar, and other modifications that they had engineered for the Boss 302.

To get the 429 between the fenders, Kar Kraft had to cut the shock towers, and move them outwards two inches. That required a wider strut tower brace. The suspension was moved forward one inch, and special spindles and control arms were fabricated to improve the car’s steering and handling characteristics because of the additional mass of the 429. A special power brake booster was needed to clear the engine’s left hand valve cover. The battery was moved to the trunk for clearance, and to improve weight distribution.

The rest of the Boss 429 package consisted of Ford’s Toploader close ratio four-speed gearbox spinning a 3.91:1 rear axle with limited slip Traction Lok. The front shovel spoiler had to be modified to clear the pavement because the Boss 429 sat one inch lower than stock height. On the hood was a large scoop that was driver-controlled to allow cold air into the carburetor. Also included were color keyed dual racing outside rear view mirrors, engine oil cooler, and chromed 15×7 Magnum 500 wheels on F60 Goodyear Polyglas GT rubber. The interior received the Black Deluxe Décor group, with AM radio standard, and an 8,000-rpm tachometer as part of the gauge package.

Aside from a Boss 429 decal on the fenders, the car’s discreet image belied the powerhouse that lurked beneath the hood. There were no stripes or other radical graphics, or blacked out trim. Exterior colors were limited to just Wimbledon White, Royal Maroon, Raven Black, Black Jade, and Candy Apple Red.

Production of 1969 Boss 429s began in January 1969 at Kar Kraft’s production facility. Kar Kraft affixed a production sticker on the driver’s door of each Boss 429, just above the warranty data plate. The first Boss 429 received number “KK NASCAR 1201”. When production ended in July, the last one was numbered 2059. Each engine block had the serial number stamped into the rear of the block, as well as the transmission housing, the chassis, and the inner front fenders. A total of 859 were assembled (including two Boss 429 Cougars), although NASCAR homologation required only 500 be built. Ford lost money on each Boss 429 because of all the modifications needed!

For 1970, the package was basically unchanged, but some minor improvements and alterations were made. The engine received a mechanical lifter valvetrain and camshaft to wake the engine up. The heavy connecting rods were replaced by lighter components to improve response. The performance of the 1969 models hadn’t been as brutal as expected given the engine size and power. Ford had purposely subdued the engine’s performance for reliability and durability (and to keep owners from getting in over their heads). The horsepower rating was still kept at 375, but with the cam change and the rear ratio, the Boss 429 became more responsive. High Performance Cars clocked a 1970 Boss 429 at 13.8/102 mph.

The Boss 429 color chart was changed for 1970 to offer Calypso Coral, Pastel Blue, and “Grabber” colors in Blue, Green, and Orange. The hood scoop was now painted black. Along with Black, White interiors were now offered in the Deluxe Décor Group. A run of 500 1970 Boss 429s were launched in August, and production was completed in December 1969, ending the Boss 429 saga.

During the 1969 racing season, Ford dominated the NASCAR circuit with the new Boss 429, winning more than half of the 54 races that season. At one point during the summer of 1969, Ford won 11 straight races thanks to the Boss 429. Unfortunately, Ford’s participation in NASCAR was significantly reduced in 1970, so the Boss 429 never achieved its true potential as a racing engine. The Boss 429 Mustang did end up on the drag strip in limited numbers, but never captured a national NHRA win.

The two 1970 Boss Mustangs shown here belong to Todd Warner of St. Petersburg, Florida. The Grabber Blue Boss 429 was built November 13, 1969, and was ordered through Ricoksy Ford in Navarre, Ohio and sold December 1. The Boss 429 engine alone added $1,208 to the Mustang’s base price of $2,872. Along with the optional Drag Pack ($155), and four-speed manual transmission ($259), other mandatory options like Competition Suspension ($31), and front power disc brakes ($65), were added for a total of $5,082. The rear wing and Sports Slats roof were installed as accessories after the car was delivered to the customer.

The Boss 302 is one of only 164 Wimbledon White cars, and is loaded with options. It’s also the source of some controversy in the Mustang community. Eagle-eyed readers will notice that this Boss 302 has air conditioning; something the order books said was not available. The Boss 302 carried an MSRP of $3,720, however, this particular Mustang was not a retail sale. Instead, it was an intra-company, “Company Lease Plan” to Ford’s Central Office Building Garage. It came complete with rear deck spoiler ($20) and SportsRoof ($65), Shaker hood scoop ($65), AM/FM ($214), and an array of other options. Instead of a retail price of $4,709, the final Intra-Office price was $3,447.

Built on September 22, 1969, it was released to Central Office on October 6. While documentation is lacking regarding the air conditioning being installed in the Boss 302 at the Dearborn Assembly Plant, there’s plenty of evidence to support the belief that it was. First, when the car was torn down for restoration in 1994, the front springs were color coded for air conditioning, not for Boss 302 use. Secondly, the build sheet calls for a clutch fan, which was not part of the Boss 302 package. Finally, the pre-drilled screw holes in the firewall used for a standard heater plenum are still pristine; there is no distortion around the holes to indicate screws were ever installed to retain a non-air conditioning plenum cover. There’s enough proof to believe it’s possible this is the only Boss 302 ever optioned with air.

by Paul Zazarine

© Car Collector Magazine, LLC.

(Click for more Car Collector Magazine articles)

Originally appeared in the June 2006 issue

Read About the 1969 Chevy Z/28 Camaro HERE

If you have a Ford Boss Mustang or another collectible you’d like to insure with us, let us show you how we are more than just another collector vehicle insurance company. We want to protect your passion! Click below for an online quote, or give us a call at 800.678.5173.

Leave A Comment