The presumption that the only real Porsche is a rear-engined, air-cooled Porsche hasn’t always been the axiom in Zuffenhausen. Point in fact; the very first Porsche built in 1948 was a mid-engine design, as were many of Porsche’s legendary sports racers like the 550 Spyder and 718 RSK. Thus it came as no surprise when a mid-engine production car entered the Porsche lineup in 1970; the 914. Still, the powerplant hadn’t yet migrated from rear to front. That wouldn’t happen for another six years.

There had been a tremendous shakeup within the Porsche organization in 1972, precipitated by disagreements among the Porsche and Piëch families regarding the day-to-day operation of the company. Ferry Porsche settled this by decreeing that no member of either family would be involved with the day-to-day operations of Porsche AG. The departure of the Porsche and Piëch families, who were replaced by a new management structure, heralded a change of direction for the company. Though Ferry remained on the Board of Directors, he was no longer running the company, per se.

“For many years I had collaborated closely with my father and was so deeply influenced by his ideas and his philosophy that I continued to pursue them even after his death,” wrote Ferry Porsche in his memoirs published in 1989. “This means that all my work bears his imprint, the result of a deep feeling of almost innate compatibility. In 1972, when the entire family withdrew from the company, the decisions taken by the new management encroached so much upon the company’s whole philosophy that they led to fundamental changes.” Whether or not they were the right decisions, Ferry saw no point in debating them. “There are many ways of reaching the right destination,” he said philosophically.

The program established by Porsche’s new management team was based on the transaxle principle, in which the engine is mounted at the front and the gearbox is linked to a live rear axle. While this reversed the fundamental tenets of Porsche engineering, Ferry wrote that, “This was nothing new to me since my father had already used it during his time at Daimler in the design of a racing car which later became the successful W25. However, it was a complete break with our earlier design principle and no longer bore my father’s imprint.” For the first time in the company’s history Porsche was about to embark on a road less traveled. The first vehicle for that journey was a car that came to be known as the 924.

From the time of the 924’s introduction as a 1976 model there were the same rumors among Porsche enthusiasts, that this too, like the 914, was a Volkswagen in Porsche clothing. And it was true, more or less. The 924 had originally been developed for Volkswagen by Porsche AG as a cheaper successor to the 914 in Europe, but when VW decided not to build it, largely because of the global energy crisis Porsche AG took over the project. The energy crisis began in 1973 with an Arab Oil Embargo against the U.S. and the West, the ramifications of which lasted into 1976, including new federal mandates, creation of the corporate average fuel economy standard CAFE, the 55mph national speed limit, and a faltering U.S. economy, among other political and economic issues, which led to Jimmy Carter’s defeat in the 1980 presidential election.

At Porsche it was decided that the company would develop a four-cylinder engine for the new car utilizing an existing VW design to economize on manufacturing, although Ferry admitted later that if the forthcoming Audi five-cylinder engine had been available at that time, they would have used it.

(Porsche Werk Photos)

The new management of Porsche AG followed the kastenprinzip philosophy, literally the building-block principle, dictating that Porsche develop both four & eight-cylinder engines. As a result, there were to be two cars, the 924 and the 928, the numerical designations chosen later in the development program to indicate the engine sizes: 924 for the four-cylinder model, 928 for the eight-cylinder car.

When Ferry Porsche’s nephew, Ferdinand Piëch, moved from VW to Audi he suggested taking the newly developed five-cylinder engine and combining two of them to create a 10-cylinder engine for the Type 928. Had Porsche done this, they would have introduced a 10-cylinder sports car more than a decade before the Dodge Viper! But Porsche had little interest in another model so closely tied to Volkswagen-Audi, deciding instead to build a V8 of its own and design the entire car in house.

Though both car programs were under development simultaneously the VW-Audi-based 924 premiered a year before the 928, becoming Porsche’s first ever liquid-cooled, front-engine sports car. The new model was assembled at Audi’s Neckarsulm plant north of Stuttgart, thus lending credibility to the presumption that the 924 was not a true Porsche. Even had the car been engineered and assembled in Ferry Porsche’s living room it wouldn’t have been a Porsche, at least not to those whose loyalty to the marque demanded an atmospherically cooled rear-engine car. But this was a creation for a new market, a new buyer; it was a Porsche for the non-Porsche enthusiast. As Ferry later remarked, “…with the new philosophy and the variants that have emerged from it we have found our clientele.”

The 924’s driveline and suspension were essentially off-the-shelf VW-Audi components modified and redesigned by Porsche engineers at Weissach to suit the specific needs of the car. As such, the 924 became a far more diversified product compared to the earliest 356 Porsches and the 914, which had relied solely on VW components. The 924’s suspension was a combination of parts derived from the VW Super Beetle, Scirocco, and Type 181 military vehicle (more popularly remembered as the VW Thing), and the engine and transaxle were an offshoot of the Audi 100 design. Everything was integrated to work in harmony and with little or no compromise, except for the braking system. The VW components dictated that the rear brakes on the 924 would have to be drums rather than discs. This was an unwelcome departure from Porsche tradition. There hadn’t been a model with rear drums in a decade, and even the 914 had offered four-wheel disc brakes. It was one piece of the 924’s jigsaw puzzle construction that wouldn’t fit. The car would be introduced with disc front brakes only.

The mechanical layout for the 924 was well under way before Porsche’s styling department gathered to discuss the exterior design. Late in 1972, chief stylist Tony Lapine set down guidelines for the new body which had to represent traditional themes, in other words, unlike the 914, the 924 had to look like a Porsche, and despite having its engine up front it could not have a grille.

This presented an interesting challenge for the design team, which was headed by Harm Lagaay, later to become chief stylist for Porsche AG. Legendary automobile stylist Sergio Pininfarina had faced a similar dilemma with the 1968 Ferrari 365 GTB/4 Daytona, the first sports car from Maranello not to feature a traditional Ferrari grille opening. Pininfarina’s solution had been to create a smooth, wraparound front fascia with concealed headlights (later to become pop-up headlights), and air intakes for the engine located below the nose of the car. This was the approach Lagaay followed with the 924. Interestingly, when the car was first reviewed in the U.S., Road Test magazine said, “There is some TR7 in front and a few thought it resembled a small Ferrari Daytona but for whatever reasons just about everyone thought it looked really slick.”

Though radically different from the 911, the 924 was immediately recognizable as a Porsche. Even the interior managed to convey a Porsche-like feeling with the dash pod containing three round gauges. The entire dash wrapped around into the doors and a large center console housing ancillary instrumentation, heater and air conditioning controls and the radio divided the cockpit. It was simple, but effective. AutoWeek magazine took a somewhat harder line, “Both the console and main dash pod are injection molded plastic, both had their fair share of roughly finished edges, and both looked — well, cheap.”

Somewhat more complicated than designing the 924 had been the actual production of the car, which was caught up in the 1974 dissolution of the VW-Porsche alliance formed during the 914 program. As a result Porsche now owned the rights to both the 924 and 928 projects outright but at a cost of nearly a quarter of a billion dollars. A new arrangement was made with Volkswagen to build the cars for Porsche at the company’s Neckarsulm assembly plant, which was nearly idle due to overproduction at VW. Though costly, Porsche AG now had total control of the 924’s design and manufacturing. Yes, it still had VW and Audi parts throughout, but Porsche had paid dearly for the right to call it its own.

Production at Neckarsulm began slowly toward the end of 1975 and in the spring of 1976 the first export market cars were being readied for shipment to the United States as 1977 models. American automotive magazines loved the 924, much more than they had the 914. The car’s handling and performance were highly praised. In fact, the 924 so surprised everyone that the only criticism Porsche felt concerned about was the car’s untraditional design and hybrid engineering. To this, Porsche’s technical director Ernst Fuhrmann replied, that the 924 was aimed at “…new clients. Among them are young people who don’t yet have a family and who can’t afford a 911 or older drivers who no longer have to transport a large family and feel like owning a sports car but are not necessarily looking for the performance of a [Porsche] 911. With the 924 we are not being unfaithful to traditional Porsche owners; we are only enlarging their circle.” And enlarge it they did.

The 928 was, by design, an entirely different sports car aimed at a very different market than the 924. The intended buyers for this new vehicle were the owners of the Mercedes-Benz 450 SL, by the late 1970s the most successful luxury sports car in the world. There were compelling reasons behind Porsche’s decision to build the 928. And one was fear instilled by the sweeping changes in the United States. The U.S. had become Porsche’s principal market. Federal changes in rules and regulations were coming fast and furious as the government took an active role in setting automotive safety and emissions standards. Detroit was scrambling to make cars that Americans wanted to buy, cars that met new government regulations, including 5-mph bumpers, while at the same time trying to bankroll all-new engineering and designs for the next half of the decade. With fuel prices rising, a see-sawing nation couldn’t decide what to buy: a big American luxury car, a sports car, a station wagon, or an import car that promised better quality and higher fuel economy. The Big Three tried to do everything, and in the process did little of it well. Screaming hysterics had taken over the U.S. automotive industry and Porsche was deeply concerned.

“There was talk of ‘tests’, of ‘procedures.’ There was quite a bit of nervousness here. Whatever the ‘rule’ they wrote [in America] we could not guess what the handling was to be,” recalled Helmut Flegl, Porsche’s Director for Research and Sport and manager of the front-engine car project. “By then we clearly knew rear-engine, air-cooled cars already did not meet their rules…. A rear-engine car just has different handling. We knew if these new rules came to life, we would have no car we could sell in the United States! It was then we knew we must make a front-engine car…”

The 928 was given priority at Porsche AG, and the design for the body handed over to chief stylist Tony Lapine, who had joined Porsche in 1969 as Ferdinand Alexander “Butzi” Porsche’s assistant. Now the former General Motors stylist faced a heroic challenge. This was not to carry on tradition, as he had been taught; this was to begin a new one! In 1977 Porsche introduced a car that achieved the goal.

I attended the 928’s American press preview at the Ontario Motor Speedway in 1977 along with Dean Batchelor who was my boss at Car Classics magazine (later to become Car Collector). What I remember mostly about that day in 1977 was remarking to Dean how strange looking the 928 appeared. I had driven many Porsches, even taken a liking to the 914/6 GT and the new 924, although with some reservations about the latter. The 928 left me at a loss for words. In my mind it wasn’t a Porsche, it lacked the sounds and sensations of a 911, yet it handled better than any of the venerable, rear-engined models I had ever driven. Batchelor, who had been with Road & Track for 16 years before becoming director of the Harrah Collection in Reno, and then Editor of Car Classics, was equally impressed with the 928. We came away with the realization that Porsche had just rewritten the book on sports car design, engineering, and performance, but we also wondered had they also cut their own throat in so doing, had they just rendered the 911 obsolete? More than 30 years later the question has answered itself, the 911 remains the most successful and endearing sports car design in history, and the front engine Porsches are gone. In 1977, however, those of us whose job it was to report on the automotive industry were thinking it might be otherwise.

The 928 was novel, not simply because it was powered by a liquid-cooled V8, but rather because it was the first model in the company’s history that Porsche had designed entirely on its own. It was, in point of fact, the first real Porsche sports car. It contained no VW parts, no Audi engine or suspension, no major component invented outside of Zuffenhausen or Weissach. To the enlightened it was an epiphany but to the traditionalists, the canons of Porsche design had been thrown out the window. To Porsche purists the 928 was an aberration. Unlike the new four-cylinder 924, which replaced the 914 as an entry-level model, the 928 was a high-performance sports car, a dissimilar but nonetheless competitive alternative to the 911 and the operative word was alternative. From a marketing perspective the company had sailed into uncharted waters with the 928 and they would either find the New World or fall off the edge of the earth.

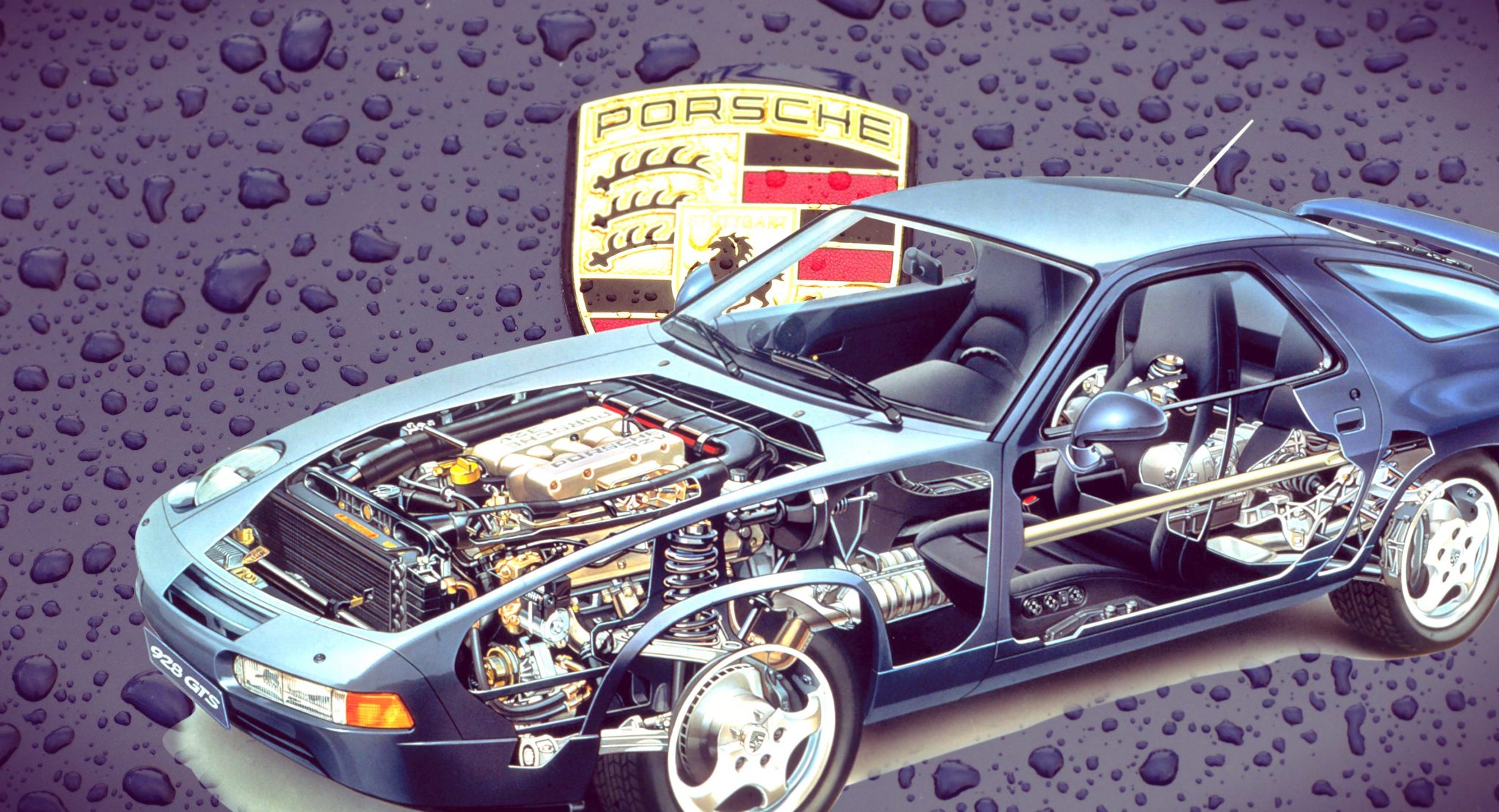

(Porsche Werk Photo)

A decade after its debut, Ferry Porsche’s assessment of the 928’s success was remarkably revealing. “The 928 and 928 S are now outstanding cars with better road-holding and more powerful brakes than the 911. They will form the basis of our model range for a long time; since there is no doubt that they still have much development potential.” As the company’s founder and Chairman of the Supervisory Board, Ferry Porsche’s glowing endorsement of the 928 in 1989 seemed to guarantee the future of the front-engine model lines, which also included the successors to the 924 – the 944 and 944 Turbo. At the same time Porsche made a point of emphasizing the continued importance of the 911, which was then in its 25th year of production. “…we would be in a very bad position today if the 911 had been discontinued. I am absolutely clear in my mind about that,” said Porsche. Though the two cars continued to travel their separate roads, just as Ferry had found a place in his heart for both, enthusiast owners were finding garage space to be shared by the 911, 944 and 928.

Since its introduction in March 1977 at the Geneva auto show, the 928 had established benchmarks for all other manufacturers of luxury GTs. The car’s groundbreaking design offered an all-aluminum engine, the extensive use of aluminum alloy in the bodywork, and transaxle layout, setting new standards in automotive engineering. Porsche’s continuous development kept the 928 at the forefront of technology throughout its 18-year production run.

Porsche’s multilink Weissach toe-correcting rear suspension, a feature of the 928 from the very beginning, marked a departure in suspension design. The Weissach axle design employed upper transverse links, lower semi-trailing control arms, and adjustable coil springs over gas pressure shock absorbers. The key to the Weissach axle was a flexible link in each semi-trailing arm, which added a toe correcting characteristic under high cornering loads. In effect, the Weissach rear axle design offered a form of “four-wheel steering” long before the concept gained popularity. A 0.89 inch (92.5mm) stabilizer bar completed the rear suspension design. The 928’s front suspension consisted of unequal length aluminum alloy control arms, telescoping shock absorbers, coil springs, and a 1.1-inch (28mm) hollow stabilizer bar.

Although the 928 was an all-new car for Porsche, it embodied 30 years of experience in designing and building sports and racing cars. The dynamic behavior of the 928 was the result of advanced-testing and experimentation, as well as experience on the racetrack. The results were an uncompromising combination of suspension, steering, and braking.

Safety considerations were also reflected in the comfort, excellent visibility, and ergonomically efficient design of the car. Safety was not a new concept for Porsche. As early as 1952 all Porsche cars were fitted with laminated safety glass windshields. In 1956 Porsche offered seat belts as an option on the 356. A 1959 racecar, the Type 718, pioneered the articulated steering column, which today is used on all Porsche models. In 1961 Porsche offered a shoulder belt as an option and in the following year made three-point belts available. Racing experience led to the introduction of plastic fuel tanks, first used in the racing only 911 R of 1967. Plastic tanks are not only impact and fire resistant, but are also impervious to corrosion. Since 1973, every Porsche has been equipped with door reinforcements for increased protection in side impacts.

The 1984 928 S was the first Porsche to be fitted with anti-lock brakes (ABS), initially as an option. ABS became standard equipment on the 928 S in 1986, and on all Porsche models beginning in 1990. Porsche’s electronically controlled limited slip differential, the PSD, capable of varying lockup between 0 and 100 percent, was also added in the 1990 model year and Porsche became the first manufacturer, domestic or import, to equip every car sold in the United States with driver as well as front passenger airbags as standard equipment.

More than a decade and a half after it changed automotive thinking, the first-class comfort, features and appointments of the 1995 Porsche 928 GTS, coupled with the model’s most powerful engine, bore witness to the 928’s status in the world of luxury high-performance automobiles.

The 928 remained in production through five series—the 928 (1978-82), 928 S (1980-86), 928 S4 (1987-1991), 928 GT (1990-1991), and 928 GTS (1991-1995), each more powerful and luxurious than its predecessor.

S of 1983. In 1985 a 5.0-liter, 32-valve double overhead cam engine with 288 horsepower replaced the original V8 design with two valves per cylinder. Output was increased yet again to 316 horsepower for the 928 S4 of 1987. The 928 GT introduced in 1989 developed 326 horsepower and displacement was again increased one last time to 5.4 liters in the 928 GTS of 1993, yielding a breathtaking 345 horsepower.

Over those years, Porsche development of the 928 concentrated on engineering with the most significant development changes to the engine and suspension. The original 4.5-liter, 219-horsepower V8 of 1978 was brought up to 4.7 liters and 234 horsepower in the 928 S of 1983. The original design, with two valves per cylinder, was replaced by a 32-valve, double overhead cam engine with 5.0 liters and 288 horsepower in 1985. Though initially for the American market only, it was later applied to all 928s. Output was increased yet again to 316 horsepower for the 928 S4 of 1987. The 928 GT introduced in 1989 developed 326 horsepower. Displacement was increased to 5.4 liters in the 928 GTS of 1993, yielding a breathtaking 345 horsepower, nearly 100 more horsepower than the 911 Carrera!

The U.S. regulations that had put the fear into Porsche never materialized to the extent that the 911 would be legislated off the American road. The 928 had leveled the playing field for the American market, only to be driven from it almost two decades later by the 911, the very car it had been created to protect.

by Dennis Adler

(Photos by the author and Porsche AG)

© Car Collector magazine, LLC.

(Click for more Car Collector Magazine articles)

Originally appeared in the April 2009 issue

If you have a unique Porsche n or another collectible you’d like to insure with us, let us show you how we are more than just another collector vehicle insurance company. We want to protect your passion! Click below for an online quote, or give us a call at 800.678.5173.

Leave A Comment