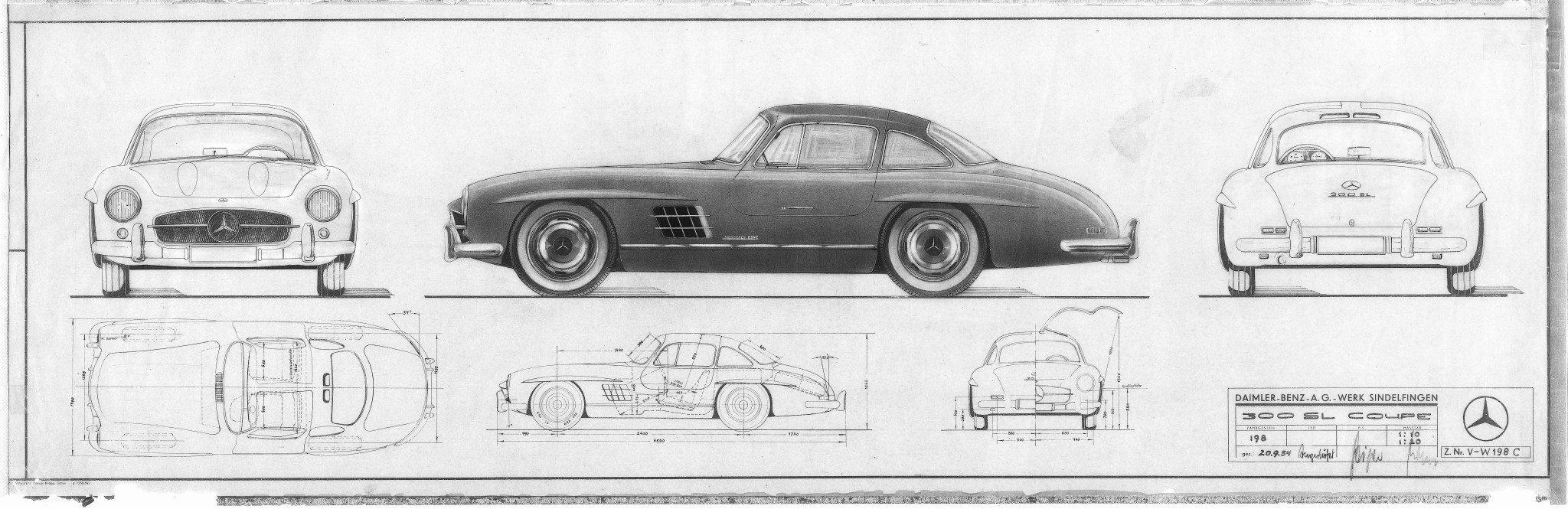

Eternal youth is a miracle bestowed on only a small number of cars, and the Mercedes-Benz 300 SL coupe is one of this elite group. From the very beginning of the European racing season in 1952, the subject of producing a road version of the 300 SL competition cars had been considered. With a little added persuasion from U.S. importer Max Hoffman, the Daimler-Benz board gave chief engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut and his staff the go ahead to turn the championship 300 SL race car into a sports car.

For Mercedes-Benz, the New York world-debut of the production version at the International Motor Sports Show (at the time America’s most important auto show) on February 6, 1954, was an unprecedented break with tradition. This was the first time in its history that the company had ever introduced a new model in the United States before its debut showing in Germany! And while New York in the midst of winter might have seemed an unlikely venue, this was the home of Max Hoffman, the man who single-handedly established the German automotive market in the United States.

With an elegant Frank Lloyd Wright designed showroom at 1739 Broadway, in the heart of New York City, Hoffman had been responsible for bringing Porsche, Volkswagen, BMW, Jaguar, Mercedes-Benz and Alfa Romeo to the United States in the early postwar era. Having seen the 300 SL competition cars win time and again in 1952, he was convinced that a road-going version would sell in the United States as quickly as Mercedes could build them. The first units of the 300 SL were sold in Europe in 1954, whilst Max Hoffman received his first customer car in March 1955. A total of 1,400 Gullwing coupes rolled off the production line from 1954 through 1957, the lion’s share of which—some 1,100 cars—found their way to the USA. Hoffman had thus assessed the response of the market to the car extremely well and had every right to be satisfied with his work.

The production version of the 300 SL captured the look, and to a great extent the performance, of the W 194 race cars but embellished it with the handcrafted luxury for which Mercedes-Benz automobiles had become renowned. The change from race car to road car demanded numerous revisions to the engine and fragile, lightweight body, yet the fraternal relationship between the 300 SL models which had swept the 1952 racing calendar and those which would sweep sports car enthusiasts off their feet in 1954 was unmistakable.

Following the New York debut, automotive reporters were falling over themselves to lavish praise on the 300 SL. Autosport reported: “The exterior form of the 300 SL is quite wonderful and its performance almost unbelievable. The construction of the car and its production quality are first class and the whole concept represents an uncompromising realization of all the new ideas.” After its initial test, Road & Track wrote: “We are looking at a car where a comfortable interior is complemented by remarkably impressive handling characteristics, quite incredible roadholding, light and precise steering, and performance levels which are up there with—and even an improvement on—the best cars the automotive industry has to offer. There is only one thing left to say: the sports car of the future has become a reality.” And Germany’s auto, motor und sport noted: “The Mercedes 300 SL is the most refined and at the same time the most inspirational sports car of our era—an automotive dream.”

The 300 SL’s racing heritage also rubbed off on to the production cars, which were accepted by the FIA for international competition in the Grand Turismo Class. With cars in the hands of privateer racers like Paul O’Shea, Mercedes-Benz continued to dominate motorsports throughout the early 1950s, as sports car racing became an American passion.

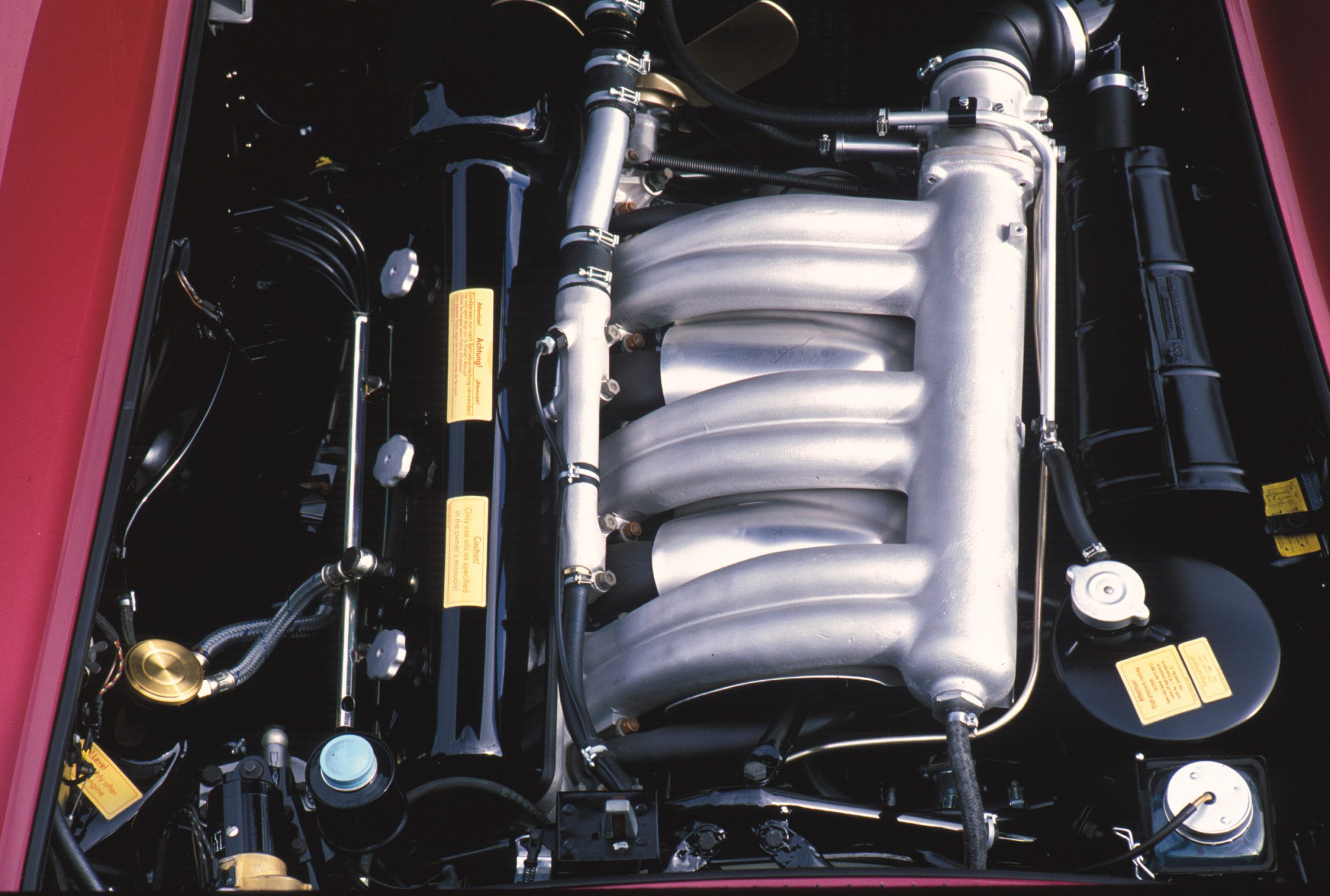

The most notable mechanical difference between the 1952 competition cars and the 1954 production coupes was the fuel intake system. The competition cars had used three Solex 40 PBJC downdraft carburetors and twin electric fuel pumps; the 3.0-liter engines for the 1954 models received fuel through direct mechanical injection, the first such application of this system in a series production, gasoline-powered automobile.

Based on their experience with diesel power, Daimler-Benz and Bosch had pioneered direct fuel injection in the 1930s for aircraft engine applications. Daimler-Benz had also experimented with a fuel-injected 4.5 liter V12 racing engine in 1939 and had even considered using direct fuel injection for the 1952 300 SL competition cars.

The 300 SL engine (as with the 1952 race cars), was a direct adaptation of the single-overhead cam, six-cylinder powerplant used in the 300 Series sedan, coupe, cabriolet, and roadster. The main differences were due to its mounting: the car’s low hoodline had forced the designers to tilt the engine 45-degrees left from the vertical in both the competition cars and the production models, so the 300 SL engine had a sloped head face, with combustion chambers extending into pockets in the block. A dry-sump oiling system also helped reduce engine height and provided better oil cooling. To assure reliability, each engine was run-in on the dynamometer for 32 hours before it was installed.

The engine’s 215-horsepower output arrived at the rear wheels via a 4-speed synchromesh gearbox and a ZF limited slip differential. At peak performance the production 300 SL could attain 150mph and reach 60mph from rest in eight seconds. For privateer competition, the cars could be ordered with a 4:11 rear axle ratio (designed for hill climbs or short American road courses) or a choice of either 3.89:1; 3.64:1 (the most common on Gullwing models sold in the United States); 3.42:1, geared for higher top speeds; or the 3.25:1, which allowed the highest maximum speed. With the 3.25 rear axle, the terminal velocity (as tested by Daimler-Benz), was a remarkable 161.5mph. Realistically, the Gullwing could easily reach 150mph, making it the fastest production sports car available in 1954.

The 300 SL, for all its power, was also a very forgiving automobile; it could be driven wide open or at a gentle pace with equal ease. The author has had the pleasure of driving several over the years, and in every instance that unique combination of might and comeliness was apparent. One could cruise comfortably at 40mph in top gear and at the whim of your right foot, be up to over 130mph in moments. Perhaps the real attraction of this car was not in your actually committing such an act, but in knowing that you could. In any case, the mechanical fuel injection played a big part in this flexibility by allowing more precise control of mixture and fuel flow over widely varying conditions.

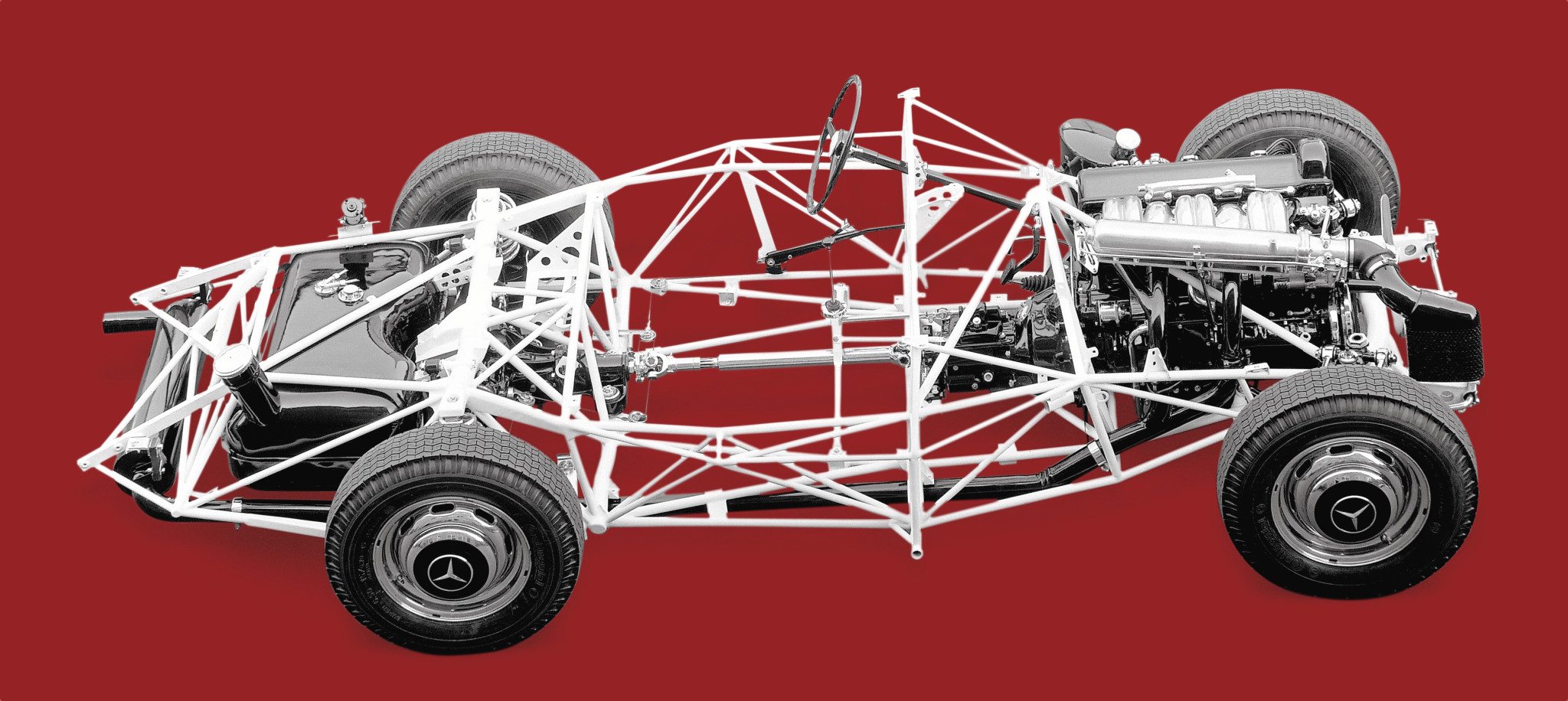

Daimler-Benz stylists Karl Wilfert and Paul Braiq had also done a remarkable job of turning a purpose-built race car into a civilized, road-going sports car, but underneath the streamlined bodywork and luxuriously appointed interior, the 300 SL was very much the same as its race-bred predecessor, utilizing a tubular frame that left a wide sill below the Gullwing doors. The means by which driver and passenger entered and, worse, were forced to exit through the 300 SL’s up-swung portals was awkward at best, although the process seemed simple enough as explained by German historian Jürgen Lewandowski:

“To enter the car elegantly, you unlock the steering wheel, swivel it to an almost horizontal position and sit down on the doorsill. Now, pull up your legs, lift them over the sill and carefully move them into the footwell. As soon as you feel properly installed, put your right arm on the right side of the bucket seat and push yourself up on the doorsill with your left arm. This will enable you to gracefully slide into the surprisingly comfortable bucket seat, then swivel the steering wheel back into its normal position.” This is probably why the 300 SL was seldom used as a getaway car.

Another complaint was the coupe’s ventilation system, or lack thereof—limited only to a cowl duct, wind wings and removable side windows. And, in general, unless one had the skills of Stirling Moss or Juan Fangio, driving the 300 SL aggressively was no easy task.

The body of the 300 SL was constructed largely out of high-grade sheet steel, although aluminum was used for the engine hood, trunk lid and the skin panels for the door sills and doors. For a relatively small extra charge, customers could choose to have the whole body made from light alloy, which cut some 176 pounds from the car’s total weight. However, only 29 SL customers took up this option and today their cars are highly sought-after rarities.

Near the end of the 300 SL’s production run, Hoffman had queried Mercedes-Benz regarding a roadster model similar to the 190 SL. He now believed an open car would be better suited to the needs of American drivers. Unknown to Hoffman, or anyone outside Rudolf Uhlenhaut’s studio, a roadster version of the 300 SL had actually been on the drawing boards since 1954; thus, in 1957, the Gullwing was replaced by the new 300 SL Roadster. As Hoffman had anticipated, it was a larger version of the four-cylinder-powered 190 SL that had been introduced along with the Gullwing in 1954. And it too, was a success in America.

As a convertible, most of the problems associated with the Gullwing were remedied, ventilation and headroom being the biggest, while an improved rear suspension made the 300 SL Roadster more manageable. The coupe had used a conventional swing-axle with two pivot-points outboard of the differential. If driven on trailing throttle through a tight curve the camber change tended to lift the inside rear wheel and induce sudden oversteer, the same problem that race drivers had encountered. This was manageable for professionals, but detrimental to those less skilled, so the Roadster was fitted with a new swing axle, utilizing a single low pivot-point, thereby improving the car’s cornering behavior and predictability.

A horizontal compensating spring included with the new axle also gave the roadster a somewhat gentler ride. Improvements in the engine compartment, including a standard-equipment sports camshaft, provided additional horsepower, making it not only a better handling car than its predecessor, but a quicker one too, despite a 200 pound weight penalty. Though not as competitive as the Gullwing, the roadster was the more comfortable and practical of the two 300 SL models. With the addition of Dunlop disc brakes in March 1961, and an optional removable hardtop, the roadster reached its highest level of development—the final evolution of the race cars that had come from the Daimler-Benz parts bins in 1952, and the imaginations of Uhlenhaut, Fritz Nallinger and Karl Wilfert. Produced through February 1963, a total of 1,858, Roadsters were built.

With its flat, graceful body, the 300 SL has lost nothing of its freshness even after 50 years. In 1999 it was voted “Sports Car of the Century.” The 300 SL Gullwing coupe and Roadster were the products of an era in Mercedes-Benz history that passed in the blink of an eye—but after half a century have yet to fade from sight.

A Brief Racing History

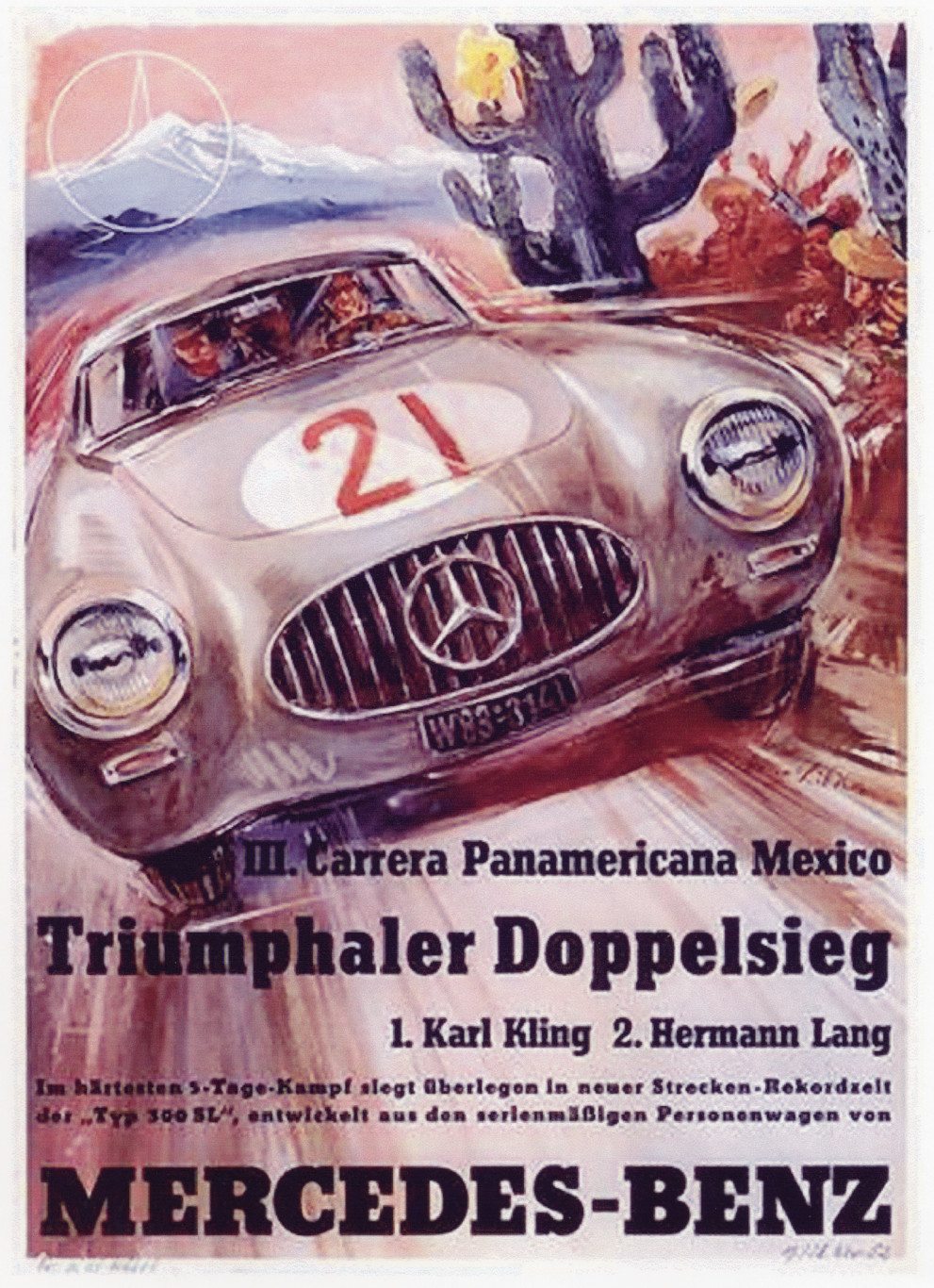

In the single year in which Daimler-Benz campaigned the 300 SL, they finished first and second in all but their maiden race, the grueling Mille Miglia, where an SL finished second, just 4-1/2 minutes behind Giovanni Bracco’s winning Ferrari. Another SL came in fourth, with drivers Karl Kling and the legendary Rudolf Caracciola. After Italy, the factory team never again saw the exhaust of another car across the finish line. Mercedes-Benz swept the first three places at the Grand Prix of Bern, where Caracciola crashed, never to race again; the team was first and second in the 1952 Vingt-Quatre Heures du Mans, and at the Nürburgring, the Mercedes team crossed the finish line first through fourth, with the debut of the car in roadster form. Virtually unbeatable wherever they ran, the factory cars wound up their racing career with a hard-fought one-two finish in Mexico’s grueling 1952 Carrera PanAmericana.

For one season, Mercedes-Benz literally dominated European sports car racing, and having demonstrated once again that Daimler-Benz quality, engineering and reliability were supreme, the cars were withdrawn from competition. There had been faster cars at every race, but none better built; the Mercedes either outran or outlasted the competition.

Jay Leno recently mentioned, “This is probably the most legendary Mercedes of all, this is the Mclaren F1 of it’s day. They always call the Muria the first supercar, and I understand that, but this one, I think, certainly deserves that title as well.” Enjoy the video below and take a look at another Heacock Classic article that attempts to define the term supercar through examining the facets of the 300sl.

by Dennis Adler

(Additional material courtesy Mercedes-Benz of America and DaimlerChrysler AG)

© Car Collector Magazine, LLC.

(Click for more Car Collector Magazine articles)

Originally appeared in the July 2004 issue

If you have an early model Mercedes-Benz or another collectible you’d like to insure with us, let us show you how we are more than just another collector vehicle insurance company. We want to protect your passion! Click below for an online quote, or give us a call at 800.678.5173.

Leave A Comment