“I was thrilled to be part of a team that created the most unique custom convertible of all times. I don’t think the car can ever be duplicated in terms of the impact it had on the custom car community.” – George Barris

Before World War II, as America was emerging from the devastating economic havoc of The Great Depression, an automotive culture was emerging. While times may have been tough, the first generation of Americans to grow up with Model T Fords appreciated these cars for their affordability and resiliency. For some, buying their first car was the ticket to ultimate personal freedom. Within that group grew a subculture that found reason to make that personal freedom a rolling statement.

Thus was born “rod jockeys,” who stripped, modified and “souped up” their jalopies. While rodding was exploding across the country, nowhere was it more prevalent than on the West Coast, especially Southern California. In the late 1930s, the sport of rodding was taking hold and birthing a new industry devoted to speed parts for Model Ts, flat head Ford engines, and other performance hardware. These hand-machined parts were crude and often times had to be reworked to fit and perform, but as demand for performance grew, the products became more sophisticated.

While others were focused on speed, another automotive subculture was emerging. For these car buffs, speed wasn’t as important as image; their ultimate goal was carrying that personal rolling statement of freedom one step further by making it unique. To them, how one’s “ride” looked as they cruised down the boulevard was far more important than how fast it went.

When these “hot rodders” came home after the war, they quickly returned to their hobby, but found the responsibilities of family, work, and home had an effect on the cars they drove. Stripped Model Ts were out. Now a ’41 Ford or Chevy coupe with a back seat for the kids was more realistic. That didn’t mean it had to be staid and boring. Soon, these cars were being lowered, their tops cut down and bodies having sections removed and dropped below the frame to lower the car’s profile. Combining parts from other cars in ways only the most imaginative person with a welder could envision became the rage.

Two brothers from Sacramento, George and Sam Barris, were on the forefront of the “custom” rage. George was the creative sibling, while Sam did the metal work. Together they built a reputation for crafting unique rides that were lower, cooler and truly one of a kind. It didn’t take long for word to spread about their wild designs and quality work.

They were drawn to the car culture of Southern California, and it was there they found themselves instantly involved in the world of customizing. The innovative concepts of the Barris Brothers soon caught the attention of rodders, Hollywood actors and customers with money and ideas, but little skills of their own. They would commission George and Sam to build the car of their dreams.

By the mid-50s, the custom car culture had changed, with wilder expressions in metal. Customizers were becoming artisans, using scallops, compound curves, scoops, panels, fins, pans, and screens for exteriors. Colors were bold, chrome was meager and stances were low and broad. Interiors were awash in roll and pleat chambers, tufted velour, colored lamps and even kitchen stove knobs for instrument panel switches and controls. There were no limits, no rules and no end to the creativity and the competition between customizers. Leading the pack was George Barris and his team of craftsmen.

What ignited the rivalry and the one-upmanship was the creation of the custom car shows and the magazines that began to write about the cars. To be acknowledged as the best by winning awards and being featured in magazines became the goal of every customizer, whether it was a professional house or a panel beater working in his garage.

“We wanted to build a winner in car shows,” George Barris said. “That’s what inspired us to do something really different.” That “something different” arrived at the Barris shop in the form of a mildly customized 1955 Chevrolet convertible owned by Bill Carr. It had already been nosed and decked. Barris added Packard lamps, fins and tail lamps, Ford side moldings and skirts.

While he was pleased with the results, Carr wanted something more. He wanted a Grand National show winner that would get as many magazine covers as possible. He was caught up in the radical custom (or “Kustom” as Barris called it) fever that was sweeping across the country.

Barris assembled his team of artisans, and along with brother Sam, Carr and Bill DeCarr, Dean Jeffries, Bob Hirohata and others, sat down to transform Carr’s ’55 Chevy into what would become the Aztec. While they borrowed heavily from both their own earlier themes, Barris felt it was time to up the bar and bring new approaches into Kustom design. “We made some different designs on everything we did,” Barris said. “Like making the fins larger and different, making the headlamps with scoops on it, carrying the NACA style scoops into the hood and changing the bumpers. Everything we did was to put together the wildest Kustom ever built.”

At the front, the fenders were widened to accept a set of Mercury Turnpike Cruiser headlamps installed under a set of air inlets. The grille opening was formed by turning a set of Studebaker lower grille pans one atop the other, with a 1957 DeSoto bumper floating in the center of a mesh grille. The hood was pancaked and a set of small air inlet scoops were molded in with a “beak” in the front panel fabricated from metal.

“I was trying to create a car that was way ahead of its time,” Barris said. “That’s why we did the floating grille and the scoops over the lights and the twin scoops that matched on the hood. It had to be totally different for a ’55 Chevy. I didn’t want to use the same grille and the same bumpers.”

Constructing these cars was labor intensive since Barris had no state of the art tools. “We didn’t have English rollers at that time or mig welders or super cutters, Barris said. “Everything we did to shape metal was done by hand. Skirts were all hand formed. We used factory parts to produce custom pieces like the oval grilles and the pans. We’d also turn them upside down to make the side pieces.”

Since Detroit’s designers were into fins, Barris decided to “outfin” the factory. They started life from a Studebaker Hawk and were quickly expanded as they were mounted on the Chevy’s quarter panels. “Everything had a purpose. It wasn’t just something stuck there; it had to conform to what we were doing for the car.”

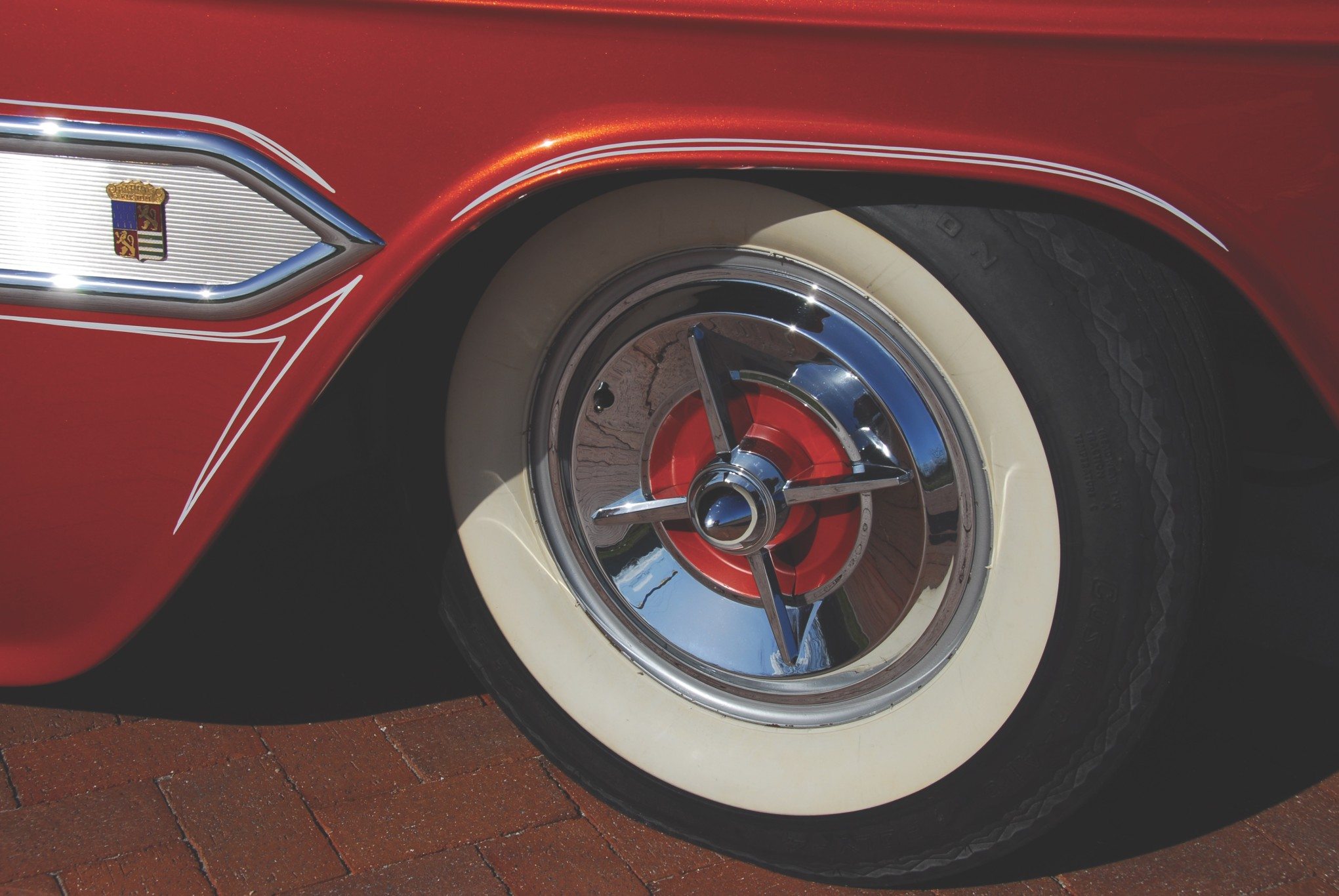

The tops of the doors were pinched to accommodate a scoop at the top of the quarter leading into the fin. A second scoop beneath it fed cool air behind the skirt to the rear wheel. To tie the front and rear together, another set of Studebaker pans were used another sectioned 1957 DeSoto bumper and mesh grille. A pair of casters was installed to prevent the lower pan from curb damage.

Once the fins were shaped and stacked, Bob Hirohata constructed the Lucite tail lamp lenses. Along the flanks, DeCarr fabricated a large chrome trimmed center spear that accentuated the height of the quarter and then narrowed, reaching to the front of the door. “The trim inside the chrome was fluted aluminum,” Barris said, “because I wanted more than just a piece of molding sitting there. I also didn’t want to two-tone it. I wanted to show that it had more character than anything we had ever done.” The fluted aluminum, commonly used in dinner car counter fronts, was popular with customizers.

To enhance the profile, Sam Barris designed a cantilever roof to replace the Chevy’s soft stack out of bar stock and chicken wire. “With a convertible,” Barris said, “you either put a Carson top on it or a folding top. I wanted to do something different, so we built a cantilever top – chopping the top and then leaving the windshield but having an open effect. We had the chrome molding off the front edge of it coming down over the rear quarter windows. The wrap around windshield was kind of hard to chop.”

The overall effect was stunning, thanks in part to the small subtle cues that combine to create a look unlike any other Kustom show car built at the time. “You’ll notice,” Barris said, “that over the headlamps and the scoops in the hood, there are little scallops around the scoops and the rear skirt and around the scoops on the rear fenders and on the ends on the fins. We didn’t make it a big flame job and big scallops going all over the place. We just incorporated a nice thin design line to pick up what we had on the car.”

Every Barris Kustom show car had a theme that tied its looks and color together, and Carr’s ’55 Chevy was no exception. “I was reading a book about the Aztec Indians,” Barris said, “and thought, ‘this is a car that really should have a unique name that’s totally different than the usual automobile model name.’ Names are very important, and that’s why I chose Aztec.”

Barris envisioned the warm earth tones of the Aztec’s desert homeland and sought to reflect that in the exterior. “The color had to be a real candy tangerine – a cross between red and orange – that had a lot of depth and reflection in it,” recalled Barris. “We didn’t want to use a sand color; it didn’t have any real depth to it to pick up the curves and the contours. We didn’t do any color blends, either. We kept it all one effect.”

The Aztec debuted at the Portland Auto Show in December 1957 and was an instant sensation. From there it traveled south to California to win Best Custom at the 1958 Oakland Roadster Show and then enthralled show crowds around the country. The Aztec crisscrossed the country five times and appeared in dozens of magazines. “It became the most photographed Kustom car,” Barris said. “It also won more Grand National sweepstakes custom awards than any other car.”

The more coverage the Aztec received, the more shows it was invited to, and the more awards and accolades continued to pour in. “We felt we had a Grand National winner,” Barris said, “not only because of the workmanship but also the design and the unique things we incorporated into the Aztec. It totally captivated audiences. The car deserved the trophies it won because of the work all of us did on it. Not only myself, but also my brother Sam, Bill Carr, Bill DeCarr, Dean Jeffries, everyone was proud to be a part of it. It won so many great awards, and we believed the car was worthy of every trophy.”

Milestone cars like the Aztec leave a lasting legacy, and its influence on the Kustom car community was like igniting a flame of creativity. “There were a lot of bits and pieces of the Aztec that came up in other customizer’s cars,” Barris said. “We saw some of the other builders like Valley Custom put a set of Stude fenders on a shoebox and others picked up little aspects of the car. Some put scoops on the side and others went into dual headlights and the Studebaker pans on the front and back. That was interesting to see they did like certain design aspects that we put into our car.”

Bill Carr had gotten his wish. He now owned the wildest and most famous Kustom car in America, however he chose to sell the Aztec in 1961 for cash and a 1961 Pontiac. Unfortunately, the buyer had robbed a bank for the cash. He was caught and the FBI seized the Aztec. It was later sold at auction and turned up in Phoenix, where it was purchased by Sonny Daout, who bought it sight unseen for $3,000.

Daout changed the interior and painted the exterior red. From there, it ended up in the hands of Warren Trappe, who planned on restoring it, but lacked the time and money, so it ended up in outside storage. That left the Aztec in terrible condition, with most of its unique custom parts removed, a far cry from the magnificent Kustom show car that had enthralled car enthusiasts across the country. Trappe came close to losing the car when the Feds again seized the car as part of a case against the storage yard. He saved the car and brought it home, where is sat in his garage. Forlorn and rotting away, the Aztec was literally held together by the master lead work done by Bill DeCarr decades before.

That’s when Barry Mazza stepped in. Mazza had been restoring old Kustoms for years and been hunting for the Aztec since 1967. He finally convinced Trappe to sell him the Aztec in 1991. What he got for $30,000 was a rusting hulk with no doors, the interior changed and floorboards gone, accompanied by the engine and most of the exterior trim. Mazza set about tearing the car apart. Since the frame, floor pans and other sheet metal were still basically 1955, reproduction parts were easy to come by. What were nonexistent were the specially fabricated pieces done in Barris’ shop. Just finding and fabricating the correct Lucite that Bob Hirohata had used to make the tailfin lenses took months.

Mazza spent years and untold treasure to faithfully restore the Aztec. Two years alone were spent on the interior. He was able to find the correct Copper Frieze and white upholstery and was able to duplicate its design from the dozens of magazine photos he had found during his research. Mazza found an original chip of paint in the glove box and had it sent out to House of Color for computer matching. Dale Worthington applied the Honey Gold Candy and Sonny’s Styling Studio retraced the intricate Dean Jeffries pin striping.

Fortunately, many photographs were taken during the original construction of the Aztec at the Barris shop, which greatly aided in Mazza’s restoration. “It made us feel so good that somebody that got it restored it back to the way it was,” Barris said, “rather than racking it up and making something else out of it. A car like that, you just can’t find another one and you can’t duplicate it. It’s historical, like a landmark.”

The Aztec and other Barris creations are to be the subject of an exhibit at the NHRA Motorsports Museum in Pomona, Calif., beginning July 11 and running through January 26, 2008. “We’re going to have a lot of my old cars at the NHRA museum this year,” Barris said. “That’s kind of nice that we’re going to have a tribute. My Grand National roadster cars will be there, along with some of Sam’s cars. I’m very proud to have it there with Wally Parks.”

Text by Paul Zazarine

Photos by James Berry and Paul Zazarine

© Car Collector Magazine, LLC.

(Click for more Car Collector Magazine articles)

Originally appeared in the July 2007 issue

If you have an early model Chevrolet or another collectible you’d like to insure with us, let us show you how we are more than just another collector vehicle insurance company. We want to protect your passion! Click below for an online quote, or give us a call at 800.678.5173.

Leave A Comment