Continental was the name chosen by Edsel Ford for Lincoln’s luxurious, custom-built 1940s coupes and cabriolets. In 1939, when the first prototype was built, Edsel felt that Continental emphasized the Lincoln’s sporty European-inspired styling. The cars were an immediate success but being virtually hand built made them a costly and exclusive model for Ford’s luxury car division. In the post World War II era the Lincoln Continental coupes and cabriolets were reprised from 1946 through 1948, (the ’46 Continental was also the Official Pace Car for the first postwar running of the Indianapolis 500) and the name was resurrected in 1956-57 for the Mk II. Continental has remained a Lincoln trademark ever since, but there was a brief time in 1955, a period between Lincolns, when the name Continental was proudly worn on the fenders of 356 Porsche cabriolets and coupes primarily sold in America by New York importer Max Hoffman. It was a one-year only (October 1954 through October 1955) moniker for the 356 Porsches. Once the cars began appearing on American roads Ford Motor Company “suggested” that Porsche not use the name because of their upcoming Continental Mark II for 1956.

The 356 Pre-A Models

The first 356 coupe was completed by Stuttgart coachbuilder Karosserie Reutter early in 1950 and Ferry Porsche anxiously took his father to examine it. “When we arrived,” wrote Ferry, “my father inspected the body closely, walking around it without saying a word and finally sitting down on a stool right in front of it. There was general astonishment; the Reutter people perhaps thought that my father was tired, when he said suddenly, ‘The body will have to go back to the workshop. It’s not right. It’s not symmetrical!’ The body was measured and indeed it was discovered that it had shifted 20mm (0.78 inch) to the right away from the central axis!” Even at age 74 Ferdinand Porsche’s eye for detail had not failed him.

With a few adjustments production was finally under way at Reutter in 1950 and Professor Albert Prinzing, (a former economics professor at the University of Berlin and head of Porsche’s management operations) called a dealer meeting at Volkswagen headquarters in Wolfsburg, where the new 356 coupe and cabriolet were shown to prospective dealers. He came away with 37 firm orders. Remarkably, the deposits paid by the VW dealers were the exact amount needed by Porsche to cover the first production run at Reutter!

The early 356 models, like the Gmünd cars before them, relied heavily on Volkswagen components. The new bodies and interiors, designed by Porsche’s chief stylist Erwin Komenda, were strikingly handsome and more streamlined than their Austrian-built predecessors but the final design wasn’t arrived at until early in 1950. Komenda and his team tried numerous variations on the original Gmünd styling. Even after the 356 body styles were finalized they remained a “work in progress” throughout the first five years of manufacture with routine changes to everything from the bumper design and windshield to the driveline, spare tire position, steering wheel, shift lever, and warm air vents. There were also to be divergences from the established 356 design tenets. The most significant was to be a run of special two-seat Roadsters under the designation Type 540 or as it later came to be known, the America Roadster. The cars were built to satisfy American importer Max Hoffman who sold 15 of the 17 Americas built in 1951-1952, this included a final steel bodied car (the rest were aluminum) also sold by Hoffman.

Coming To America

Sales in the burgeoning postwar U.S. market were of considerable importance in the early 1950s and Ferry Porsche found a kindred spirit in former Austrian automotive entrepreneur Max Hoffman. Failing to embrace the political views of Hitler and the Nazi regime, Hoffman had moved his automotive business to France in the late 1930s. Two days after Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, both England and France declared war on Germany, and Max Hoffman decided it was time to catch a steamship bound for New York. Like Luigi Chinetti, Sr., and Rene Dreyfus, among others who were in the United States when our nation was drawn into the war, Hoffman’s visit to our shores became permanent. In the 1940s he became a successful manufacturer of costume jewelry, having found a way to produce elegant and affordable bobbles made out of metal-plated plastic. His first week in business, Hoffman booked $5,000 in orders! By the time the war was over in August 1945 the auto salesman-turned-jeweler was ready to begin doing what he knew best, only instead of importing American and British-built cars to Europe, he was going to bring the best that the Continent had to offer to the United States. He established a posh Park Avenue dealership in the heart of New York City and began importing British and French sports cars. Not far away, Chinetti was busy establishing himself as the sole American importer for Enzo Ferrari’s new postwar sports and racing models. By the early 1950s if you wanted an exotic foreign sports car, New York was the place to go.

Ferry Porsche and Max Hoffman had met by chance at the 1950 Paris Motor Show and immediately hit it off. Hoffman wanted to import Porsche’s new VW-based sports cars (Hoffman was also importing Volkswagens and BMWs) and Ferry Porsche regarded the U.S. market as essential to his company’s future. Hoffman had already heard good things about the 1948 Gmünd Porsche sports car from his friends in Austria, and he had known Anton Piëch (Porsche’s brother-in-law) since the 1930s. Max believed that the 356 coupes and cabriolets would be a big hit in the American market. And as in most things automotive, he was absolutely right.

The cabriolet was Porsche’s top-of-the-line model and 1952 was the first year that Hoffman offered it for sale in the U.S. This was the luxury Porsche. In Germany it was referred to as the Dame or Damen, literally lady or queen, and came equipped with the 1500cc engine (also later 1600cc engine) a fully upholstered and carpeted interior, more comfortable seating, a convertible top with a full, padded headliner, and amenities such as an interior dashboard light, and an optional Telefunken (tube-type) radio with push-button tuning. (Dame or Damen was also used to denote 1500cc and 1600cc coupes not fitted with the more powerful Super engines.)

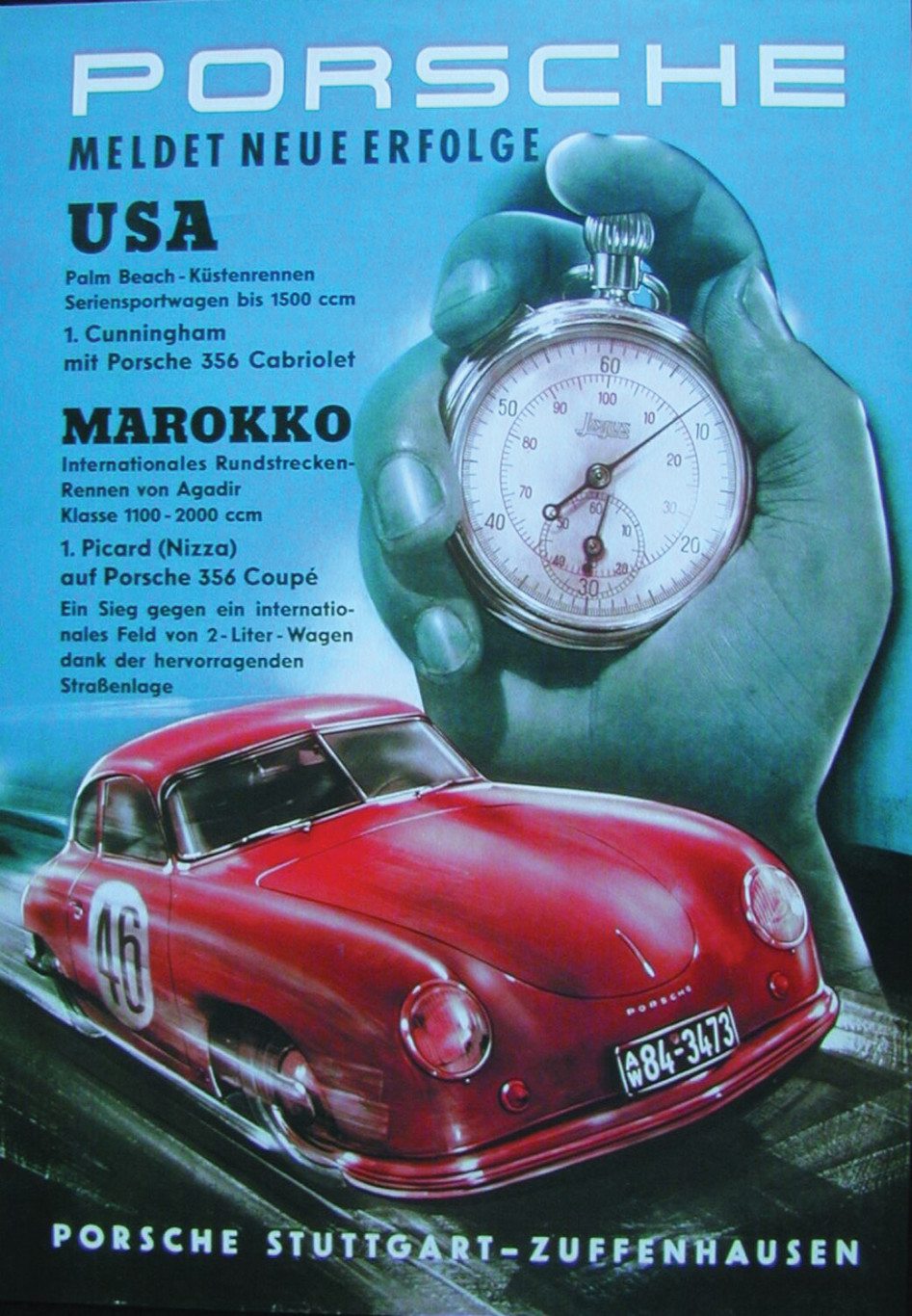

In the 1950s Hoffman was the sole importer of Porsche products into the U.S. He had told Ferry Porsche that Americans didn’t buy cars with numbers – only cars with names – and he suggested the 1955 models should all have names. He had already established this precedent with Porsche’s limited production America Roadster in 1952 and with the 1954 Speedster, a stripped-down, low-priced 356 roadster only offered in the U.S. at just $2,995.[1] For 1955 he convinced Porsche to badge the 356 coupes and cabriolets as the “Continental” to reflect their European origins. Perhaps Max Hoffman was channeling Edsel Ford. Interestingly, by the time Ford Motor Company noted their objections, Karosserie Reutter had already punched holes in about 200 sets of front fenders! The Pre-A coupes and cabriolets were already wearing the “Continental” nameplate. In addition, the earliest 356A models, introduced late in 1955, also had fenders punched with nameplate holes. The quick fix was a switch from the gold-colored Continental script to the name European on early 1956 models.

The so-called “Pre-A” designation was added later in Porsche history to distinguish the new cars introduced in October 1955 from earlier 356 coupes and cabriolets and the very first Speedster models built in 1954. The Pre-A cars (coupe and cabriolet) are actually more interesting to examine because of their unique styling traits, which differed noticeably from the 356A versions. One of the more distinguishing characteristics was the rear fender treatment, which had a wider, more graceful wheel arch, covering more of the tire. Other production changes that occurred during Pre-A production, particularly in 1952, included redesigning the bumpers, which were originally integrated into the body until October 1952 (1953 models) after which bumpers were separate pieces mounted through the body as seen on the 1955 Continental cabriolet pictured from the Barry and Glynette Wolk collection. The first use of separate bumpers was on the America in 1951-52. Other running changes included replacing the original split windshield with curved, one-piece glass beginning in March 1952, and dropping the temperamental 4-speed crash box for a new synchromesh transmission in 1953. The 1952 models were also among the first to come equipped with the more powerful 1500 Super motor (beginning in March 1952), upping displacement from 1.3 to 1.5 liters (91 cubic inches). The smaller VW-based 1100cc engines also remained available through the 1954 model year. The engines in the first production cars had been modified VW motors fitted with new aluminum cylinder heads. Porsche increased the flat four’s swept volume to 1488cc by lengthening the stroke 10mm and using a new die-forged Hirth[2] crankshaft. Bore x stroke were now 80 x 74mm, however, at 1.5 liters the VW engine had been taken as far as its design would permit. Porsche would have to begin building their own engines if they wanted to go beyond the 1.5 liter’s capacity. Chief engineer, Dr. Ernst Fuhrmann, had already begun to tackle this problem in 1950 under the product designation Carrera, the Spanish word for race, which by the end of the decade was to become synonymous with the Porsche name.

Badges

Back in 1952 the first steps were being taken towards creating a Porsche emblem or a coat of arms. “Max Hoffman had been urging us to do this for some time,” recalled Ferry in his memoirs. “He cited the example of the English and said what beautiful emblems they had and that we should produce something similar. He considered this important for the American market. He made the suggestion to me one day while we were lunching together in New York and I quickly sketched out a piece of heraldry on a napkin. I said to Hoffman as I was drawing, ‘If all you want is a coat of arms, you can get one from us!’” Ferry then sketched the crest of the House of Württemberg and in the middle put the coat of arms of the city of Stuttgart: a rampant horse, above which he placed the Porsche name. (Enzo Ferrari had also used the rampant horse for his personal emblem since 1923, when the Countess Paolina Baracca presented the Stuttgart coat of arms to Ferrari after his victory in the Circuit of Savio race). Upon his return to Stuttgart, Ferry gave the napkin to Erwin Komenda and asked him to draw a clean copy. “We then took the design to the state government and the City of Stuttgart and requested that they authorize the design for use as our emblem. The authorities raised no objections, and so from 1953 onwards Porsche cars bore their own emblem, to the great pleasure of all concerned,” said Ferry. Today, both Porsche and Ferrari still use the rampant horse as part of their company emblem.

This 1955 Pre-A continental (one of only 10 in the world known to have survived) marked the end of a brief era at Porsche. In the Fall of 1955 Porsche unveiled the new 356A series at the Frankfurt auto show. The newer styling was accompanied by an improved engine under the vented rear decklid. The higher-performance push rod engine offered in the 356A was a new, more powerful Porsche version with a swept volume of 1.6 liters (1582cc) available in either 1600 or 1600 Super versions. Their greater displacement allowed Porsche to increase compression ratios, taking full advantage of the newer high-octane fuels available in the mid-1950s. The 356A also fit nicely into the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (F.I.A.) class established for 1600cc touring and grand touring cars, putting Porsche in an even better position for sports car competition. With the new push rod 1600s, Porsche could stress smoothness and flexibility rather than sheer neck-snapping power. This was possible because Porsche engineers had also improved the body, chassis, and running gear on the 356A. Among the changes was a new tire/wheel relationship; tires of smaller rim diameter and larger section (5.60 x 15 rather than 5.00 x 16), were fitted with lower recommended tire pressure. In concert with the new tires, strengthened steering tie rods and ball joints were utilized. The position of the steering linkage was also changed to impart a roll understeer effect – a slight steering outward of the outside front wheel when the car leaned into a turn – and the caster angle was doubled. This reduced some of the tendency for the car to swap ends when driven hard into a turn. Thus the majority of changes introduced with the 356A had to be experienced, rather than seen.

From behind the wheel the 356A was a decidedly different car from its predecessors, and not only in performance and handling. The floorpan had been lowered 1.4 inches by doing away with the false floorboards previously used. The handbrake design was changed from a ratcheting lever mounted to the left of the steering column to a twist release mounted on the body (under the dash). The dashboard was a completely new design positioning three large gauges directly within the circumference of the steering wheel – speedometer to the left, tachometer in the center, and combination fuel and oil temperature gauge to the right. An interesting footnote to the new design was the use of foam rubber padding under the dashboard cap upholstery, one of the first modern attempts to add a safety feature to interior design.

Now, more than half a century later, when we look at the earlier Pre-A dashboards like this 1955 Continental’s, there is an old world sense about them, a kind of prewar hand craftsmanship that was lost on the 356A dash. Maybe that’s just nostalgia talking. In 1956, a year after the 356A models were introduced the sales office estimated that 70 percent of all Porsches produced were being exported, with the majority being sold in the United States. Max Hoffman was right again.

******

Our special thanks to Porsche historian and author Dr. Brett Johnson for his assistance in preparing this article.

To learn more about the Pre-A cars you can order the author’s book Porsche – The Road From Zuffenhausen from Amazon.com. Other recommended reading includes The 356 Porsche by Dr. Brett Johnson, and Original Porsche 356 by Laurence Meredith.

by Dennis Adler

© Car Collector Magazine, LLC.

(Click for more Car Collector Magazine articles)

Originally appeared in the January 2009 issue

If you have a 356 or another collectible you’d like to insure with us, let us show you how we are more than just another collector vehicle insurance company. We want to protect your passion! Click below for an online quote, or give us a call at 800.678.5173.

Leave A Comment