From a Rudimentary Appendage to a Major Styling Element, Fenders Helped Define the Era in Which a Car Was Built

At the turn of the last century it was almost impossible to have a “fender bender” because there weren’t any fenders, but that was just a temporary situation. By the early 1900s just about every American and European made motorcar had rudimentary fenders of some form over the tops of the wheels to keep mud from being slung into the faces of the driver and passengers. This worked some of the time but dusters, hats, and goggles were recommended accouterment for the open road.

It is believed that the first automobile fender was invented in 1901 by Frederick Simms, who was instrumental in the founding of Daimler in Great Britain (1893), as well as the Automobile Club of Great Britain in 1897 (later the RAC). One could beg to differ, since Carl Benz had already mounted cycle fenders on his Patent Motorwagen by 1894, and the 1898 Benz Ideal had full length fenders. In the United States the earliest cars to have fenders, which were little more than mud guards, began to appear by 1903-04.

By the mid 1900s fenders were finally becoming more than appendages. Both their length and width were increased with many curving all the way down to the frame. Soon the front and rear fenders were joined together by a sturdy running board that paralleled the frame line. This became the preferred style for more formal cars in the early 1900s, while sportier models eschewed the running board. By the 1910s just about every car built in America and Europe had some form of fender and running board combination, and fenders themselves were beginning to take on a more stylish appearance, some rakishly curved, others flared at the rear to further prevent the splash of American roadways into the passenger compartment of open cars. But fenders were still rudimentary in their overall design. Body stylists regarded them as a necessary feature but one relegated to a single job, keeping the road beneath them, beneath them. Whether a handsome cycle fender design, a flat-topped wing, or long, sweeping fender-into-running board style, rarely did fenders add anything dramatic to the overall look of an automobile.

American manufacturers had all achieved a near equal level of engineering refinement and reliability in their products by the early 1920s, but bodywork was mostly provided by outside coachbuilders, and that coachwork was generally accompanied by similar elements: running boards, fenders and mudguards, all separate components, and all very much the same in appearance. Then one day a designer said something to the effect of, “…if we extended the front fender rearward and added a recess at the bottom, you could mount the spare tire there.” It is likely those words were spoken by Harley Earl, since the design began appearing on La Salle and Cadillac production cars in 1927, less than a year after he was hired by General Motors to create Detroit’s first automotive styling department at the suggestion of Lawrence P. Fisher. Fisher was Cadillac’s General Manager, and something of an aficionado of Earl’s work for Don Lee.

The side-mount spare wasn’t a new idea. Companies like Locomobile had been offering them since the early 1900s, but back then side-mount spares precluded using one side of the car as an entrance for the driver. The same was true of Oldsmobile, Packard, and Pierce-Arrow, among others by the 1910s. Interestingly, in 1919 Earl had already penned the innovative fender-mounted side-mount spare, which was used for a coachbuilt Duesenberg Model A sedan bodied at the Earl Automobile Works in Los Angeles. The company, founded by Harley Earl’s father, was owned by Don Lee, Southern California’s premier Cadillac dealer. Earl had also designed and built several custom bodied Cadillacs for Don Lee in 1921, all of which featured fender-mounted side-mounts. Soon other American coachbuilders were following suit, including Judkins and Fleetwood, but the majority of coachbuilt cars bearing this distinctive fender line were coming from Don Lee Cadillac and the drafting table of Harley Earl.

The new side-mount design, whether pioneered by Earl or someone else had changed everything by the late 1920s, including the fender itself. The greatest changes, however, were to come the following decade when fender lines became as much a styling element as hoods, rooflines, windshields, trunks, and even headlights.

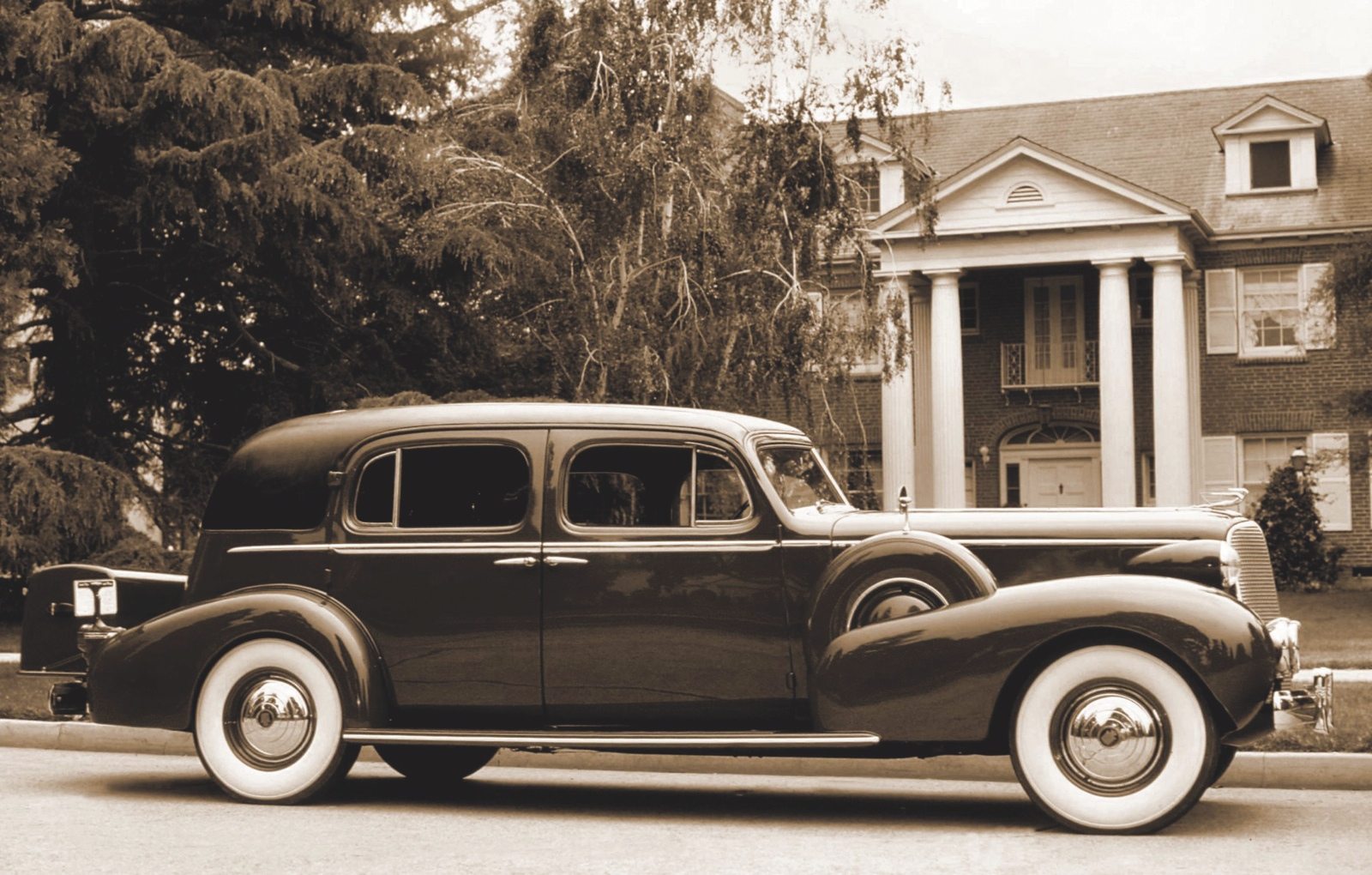

For Earl and Cadillac (and other GM Divisions) the first dramatic change in fender lines came with the 1933 models and the introduction of skirted fenders, a design which swept the American automotive industry from Packard to Pierce-Arrow. By 1934 Lincoln and other U.S. automakers were all featuring skirted fenders. Of course by ’34 Earl had already redesigned the skirted fender introducing the pontoon fender look, which made the fender an even more prominent styling element. Variations of this design would carry GM through the 1930s with the most significant changes coming in 1939 from the drafting table of Earl’s protégé Bill Mitchell. As the decade came to a close, the influence of Harley Earl’s 1938 “Y Job” concept car was spreading throughout GM and the American automotive industry. The “Y-Job” was not so much a look at the distant future of automotive styling but a glimpse about three years ahead. The hoodline, integrated fender lines and general contours would begin appearing on GM models beginning in the WWII abbreviated 1942 model year and being reprised in 1946.

While Earl’s “Y-Job” was changing the shape of fenders in America by the end of the 1930s, in France, fenders were changing the entire shape of cars! From the armistice in November of 1918 to the onset of World War II in 1939, the styling and construction techniques employed by French coachbuilders were among the most advanced in the world. Their flamboyant, avant-garde, almost larger-than-life designs were the envy of every automaker. As famous as their clienteles, Jacques Saoutchik, Joseph Figoni, Henri Chapron, Letourneur et Marchand, Jean-Henri Labourdette, and the Franay Brothers, all at various times, and on a variety of both European and American chassis, fashioned some of the most magnificent body designs of the entire 20th century. By the early 1930s the society of ateliers on the outskirts of Paris were a hotbed of activity with France’s leading carrosserie catering almost exclusively to national marques such as Talbot-Lago, Delage, Delahaye, and Bugatti. The most influential stylists of the era, at least as far as fender lines are concerned, were Jacques Saoutchik and Joseph Figoni. Their work on Talbot-Lago, Delahaye and Delage chassis completely redefined the shape of automobiles built in France during the late 1930s. Figoni’s work on late ’30s Talbot-Lagos and Delahayes stands out as some of the most innovative if not outlandish of the entire 20th century. One would have to search high and low to find more intriguing designs than the Talbot-Lago T150 SS “Lago Special” models or the 1939 Delahaye Type 165 V12 Cabriolets.

With the Talbot-Lago T150 SS Figoni perfected his aerodynamic design theory with a streamlined body composed almost entirely of curves, the car’s teardrop shape dictating even the contour of the doors, which were oval. The entire body of the T150 SS was a study in prewar aerodynamics. Figoni had first experimented with this design in 1932, although on a much larger scale, for a Rolls-Royce Phantom II Pillarless sedan. For 1939 Delahaye management decided that the company needed to do something spectacular, and that something was a V12 engine on a Type 165 chassis fitted with a one-off body by Figoni. Given the proportions of the massive Cabriolet, the 165 appeared larger than life, literally and figuratively. Only one example was completed, and a second non-running display car shown at the Paris Salon. (That car is now fitted with an engine and is fully road worthy). Bodied as a two-seater, which was the competition formula (most Delahayes were designed to seat four or five), the Figoni Cabriolet was one of the French designer’s more seductive aerodynamic motifs. As with nearly all Delahayes designed by Figoni, the bodywork characterized the image of captured motion – just a trace of windshield frame, which could be cranked down completely into the cowl if one desired, chromed sweeplines slashing through the hood and doors, and bold, elliptical fenders that gave the body a sense of fluidity, as though being stretched rearward by the force of its speed. The Figoni Delahaye left most everyone at the 1939 Paris Salon speechless. It is much the same today whenever the cars appear in public. When you consider just how much changed in automotive design between 1900 and 1939, and the significant a role that fenders played in bringing about those changes, you may never look at a fender in quite the same way.

Fender styling and side-mounts took on a familiar look in the early 1930s whether on a Cadillac, a Packard, or as pictured, a Chrysler CG Imperial, Duesenberg Weymann LaGrande Torpedo Phaeton, or Model J Derham Tourster.

by Dennis Adler

© Car Collector magazine, LLC.

(Click for more Car Collector Magazine articles)

Originally appeared in the April 2009 issue

If you have a unique collectible you’d like to insure with us, let us show you how we are more than just another collector vehicle insurance company. We want to protect your passion! Click below for an online quote, or give us a call at 800.678.5173.

Leave A Comment